Hello. How are you? (Click Email to let me know).

I’m a writer and filmmaker based in Vancouver, BC.

HERE’S MY REEL

On my filmmaker side I make narrative films and music videos. On my writing side I’ve published short stories, essays, and book reviews. I’ve also written novels, feature screenplays, and film theory that are just sitting on my computer as of now but I’d like to publish them too one day. That would be so cool. I love writing.

I’m currently researching and developing a feature film with the support of the Canada Council for the Arts.

You can read essays I’m writing as part of my research here.

I graduated from the University of British Columbia in 2018 with a BFA in Film Production and a Minor in Literature. Since then, I’ve been in VIFF’s Catalyst Program and had my work shown in festivals across the country and my writing published in magazines distributed all over North America. I’m now pursuing my MA in Cinema Studies at UBC.

This is really fun for me and I like doing it. I’m going to keep doing it. Thanks for reading. (Click Email to say you’re welcome).

Contact Me

You’ve Probably Never Heard of It

On Esoterica, Obscurity, Infinity, and the BeyondThe first film that I ever watched illegally was Andrei Tarkovsky’s Solaris in high school. It was on a website that doesn’t exist anymore. The video player was imbedded in a distorted clip art image of a movie theatre, and there was a button you could press to turn the lights off and on. When you turned them off, some cartoon audience members appeared. I distinctly remember one throwing popcorn at the screen. I kept the lights off, but it’s not like it really enhanced the image, which itself was compressed and pixelated and, I realized later, after finally seeing the film in a 4k restoration, even cropped by the necessities of the clip art frame.

It kind of looked like this

I remember watching the film which, by its own merits, obliterated my understanding of what films are supposed to be like, feeling wrong in itself, and feeling doubly and indelibly wrong from the way I was watching it. Not just because this version was so far removed from the beautiful images that were originally intended, but because, while dodging advertisements for porn sites, erectile disfunction medication, and online gambling, trying desperately to ignore the crudely inserted cartoon man laughing in the front row, the fabric of the film felt fragile, obscured, and wildly inaccessible. I was already taking a leap into a dimension of filmmaking that I didn’t really understand, an echelon of artistic expression that felt so beyond what I was used to. Now, the very texture of the experience was sharpened to barbed points of inaccessibility. To this very moment, Solaris is coloured acutely in my mind from that original viewing by the sensation of “off-ness,” by the fragility of a corrupted image that is a crude facsimile of a former, emboldened, cosmic self. This perception pairs perfectly with the plot of the film but is nevertheless a perversion of the wishes of a director who emphasized the majesty of the image. That image was deteriorated, unsanctioned, and illegal. Viewing it as a member of the generation to whom it was explained that, since I wouldn’t steal a car or a handbag or a television I shouldn’t pirate films, and in viewing the film as someone who definitely holds true Tarkovsky’s sentiment that: “Art has a distinct spiritual value,” I really feel a sense of profane instability connected to Solaris, in fact to any film that I watched on any of the backwoods sites that were so strange and plentiful in the 2010s.

And, with the statute of limitations now passed, I can admit that I watched a lot. A lot. I didn’t have a revue cinema (that I knew of) to frequent growing up, the only DVD store I knew around me was the now defunct Rogers Video. Art Cinema was widely available but I only encountered it on the Putlockers, Solarmovies, Gorillavids, and PopcornTimes of the world wide web. I think there’s something perfect about this. These movies, which fought so diligently and beautifully against the normative laws of cinematic narrative, didn’t belong in Cineplexes. They felt unstable, because they were unstable -- shifting, warbling mirages of traditional filmmaking, cut up and distorted films that felt wrong because they were wrong, films that disturbed my innate sense of narratological rhythm, that perverted my instilled understanding of what film should be, and that floated listlessly in the unsanctioned international waters of the internet, waiting to be discovered by those who journeyed to find them.

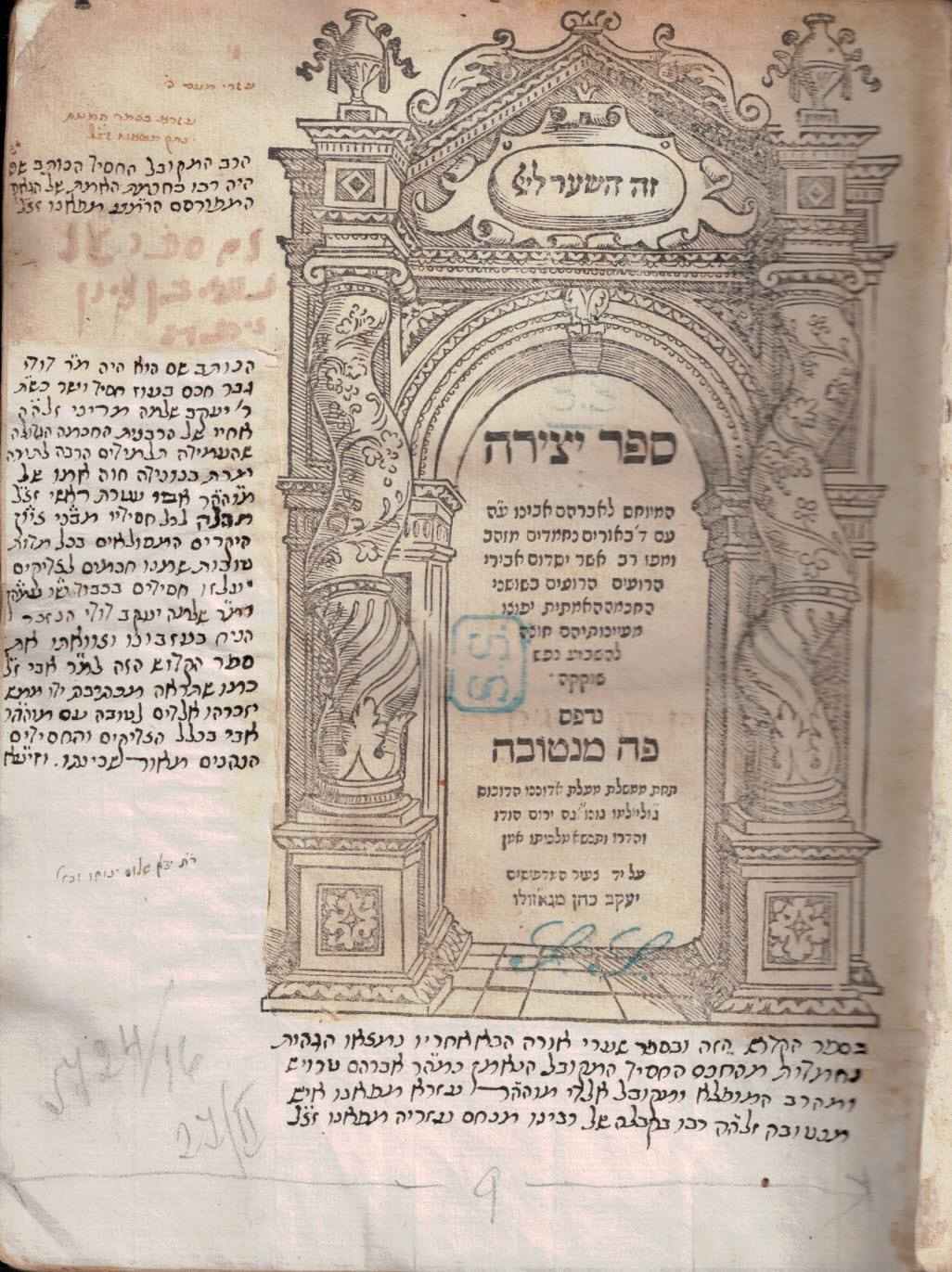

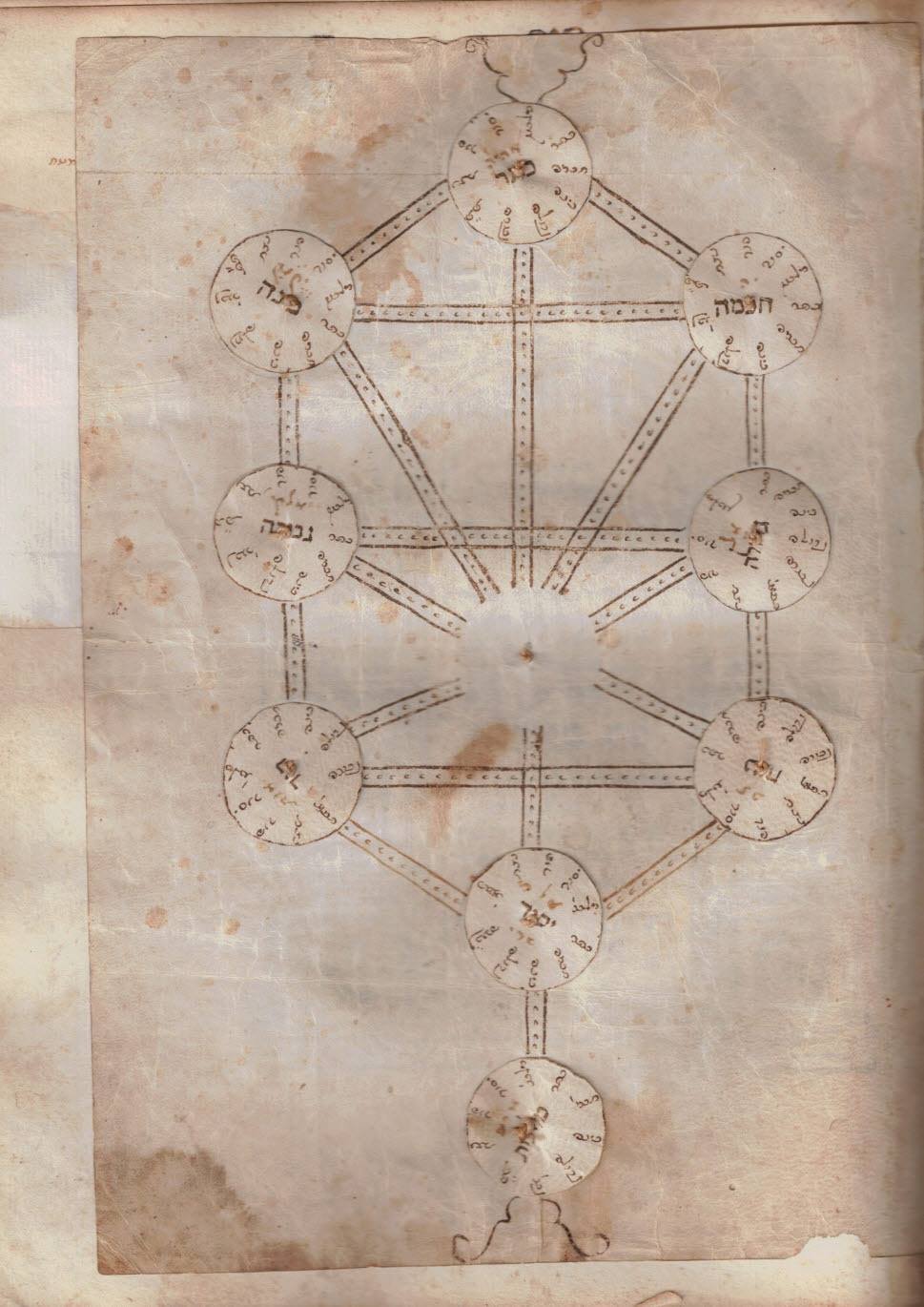

I’m thinking about that Solaris experience because of two books sitting beside me right now which I’ve hardly read at all. Every time I do, I feel kind of weird. We’ll come back to my dark web cinematheque in a minute, but for now we can glance at (not quite turn to, not quite dissect) the Zohar and the Sefer Yetzirah. I personally own Gershom Scholem’s selected readings from the Zohar and Aryeh Kaplan’s Sefer Yetzirah: In Theory and in Practice. Both are selections and commentaries on monumental texts that make up the Kabbalah, perhaps the two seminal texts. They contain gorgeous cryptic infinities, the same obliteration that art cinema levelled at commercial film, this time directed at the genre of religious exegesis. I read an okay amount of Talmudic commentary in Jewish elementary and high school, more than your average Jew who never wanted to be a Rabbi, I guess, and certainly listened to plenty of sermons from Rabbis, youth group leaders, teenagers, and Bar and Bat Mitzvot. These books aren’t like them.

The Zohar, the Book of Splendor, is the central book of all the various Kabbalist systems. It contains multitudes, to put it mildly, but is essentially a sort of mystical novel, surrounding the teachings and conversations of Simeon Bar Yochai, who lived over a thousand years before the Zohar was first published. Through this avatar, and in poetic, illustrative, nearly maximalist language, the Zohar delves into mystical commentary on the Torah, the origins of the universe, the structure of God, and the life of the soul. As enormous and imposing as the Talmud, the Zohar was frequently seen as a distraction in the Yeshivas (theological seminaries of sorts) of Europe, with scores of students electing to study its mysterious contents as opposed to the hard-lined rationalism of the books of the Talmud.

Though the origins and makeup of the Zohar are mysterious and still garner debate, the origins of the Sefer Yetzirah, the book of creation, are ensconced in even thicker darkness. Lacking even a definitive version, the Sefer Yetzirah is purported to have been written by either the patriarch Abraham or by Rabbi Akiva, which places its legendary origins into a timespan of around 2,000 years, with references to it appearing as early as around 500 A.D. Scholars confidently place it as being written sometime in the 1st Millennium. However helpful that is. Its contents are a bewildering spectrum of a numerico-linguistic breakdown that attempt to describe a thesis on the powers of mystic creation. It is taciturn, terse, and commanding, and carries with it a reputation of magic, legend, and heresy.

With this essay, I’m going to attempt a reflection on the sensations of reading, holding, and studying these books, and will focus less on the actual material of their sources. These texts are famously complex and confounding. They don’t give up their secrets easily. Not that I’m necessarily after these secrets, but the very existence of secret knowledge that forced the traditional canon of Judaism to eschew these books, charge them with a radiating danger of sorts. All religious esoterica feel that way to me, and encountering them feels perverse, apprehending their mystique, standing at the precipice of whatever secret knowledge they contain feels like standing at the edge of a cliff. What awaits you at the bottom?

It’s not like I necessarily invented the “danger” that I sense from these books. A common refrain known by Jews is the prohibition on studying the Kabbalah until you’re 40 years old. I inherited this tradition, with the extra incentive that reading it too early would kill you or drive you insane which, perhaps perfectly, imbued the books with a magnificently dangerous magical power. And seeing as my inquiry into Judaism is an effort to reclaim those images and sensations in which my religious experience first opened, the religious fear that throbs from the countless texts that orbit the Kabbalah as a consequence of that prohibition made this the first subject to which I gravitated. And so, I bought these books before I bought any other, albeit with intense trepidation. And even with that act, I didn’t even buy the books themselves. I had to cover them up with a greatest hits edition and a critical analysis.

Until these books, I read sort of around the Kabbalah, I saw the aura of the light of its fire from around the corner. Like staring into an eclipse, I approached the Kabbalah as a reflection through a camera obscura. And even with these books, I’m not really fully approaching the Kaballah. The selected readings from the Zohar that I own is 95 pages long. The 2018, full English translation of the Zohar comes in at 7,792 pages. The depths out of which my slim copy of the text springs is yawning and echoing and I can feel its immensity, even in the scant selections that emanate from it. Inversely, the Sefer Yetzirah, in its longest version, is 2,500 words, shorter than this essay, while Aryeh Kaplan’s expounding on its teachings and implications is 300 pages long. The Sefer Yetzirah is a vast spectre in its brevity, a swirling galaxy of numbers, letters, cosmic mathematics and linguistics in a nigh-on psychedelic Mandelbrot set of infinity, and the expansion of this text into one 30 times its length obfuscates the immensity of that monument, obscuring its painful aura.

But is it just that prohibition that makes these works so awesome and frightening? Is it just superstition that triggers that anxious Jewish failsafe in me? Or is it the literal, spiritual value of the language of the text, its reputation, abilities, the cryptic qualities of its aesthetic and formal inventiveness? Or is it the power they gained in obscurity, after that prohibition obscured, occulted, and esotericized them?

We’ll answer all these questions, but first we’ll look at that prohibition, which I think certainly amplifies the power that these books hold over me. Here, we’re talking about the books, not just the matter contained within them. Like I said, I’ve read around these books. I’ve read summaries, explanations, commentary, and history, all of which contain direct quotes from these books or from mystics that interpreted on them. But it’s the object of these books that throbs that painful aura.

We can certainly read the Rabbinic prohibition surrounding Kabbalah with Georges Bataille’s theory on Taboo and Transgression (see my essay on the Occult). But using the word “aura” brings us right to the feet of German-Jewish critical theorist Walter Benjamin, and I’ve been really looking forward to having a dialogue with him in my papers.

In Benjamin’s authoritative treatise, “The Work of Art in the Age of Mechanical Reproduction,” he sought to diagnose the powerful, phenomenological aesthetics of a work of art and the growing trend in post-industrial society to devalue that power. Benjamin saw that technical reproduction (particularly photography) strips the work of art of its uniqueness and the quality of its time and place. “In even the most perfect reproduction, one thing is lacking: the here and now of the work of art — its unique existence in a particular place. The here and now of the original underlies the concept of its authenticity… The whole sphere of authenticity eludes technological reproduction.”

Marking the history of art from “figures in the service of magic,” like the prehistoric bison drawings in the Chauvet Cave, to a secular l’art pour l’art, art for art’s sake, like a Futurist sculpture, Benjamin marks a de-reverential sensibility, concurrent with the secularization of Western society. This secularization leads to public spectatorship of any artwork in non-ceremonial exhibition and eventually reproduction of the work in photography to disseminate its likeness with abandon.

“An ancient statue of Venus, for instance, existed in a traditional context for the Greeks (who made it an object of worship) that was different from the context in which it existed for medieval clerics (who viewed it as a sinister idol). But what was equally evident to both was its uniqueness – that is, its aura.” The aura of that statue extends from its uniqueness and location, both physically and culturally. Venus’ aura extends out of its role as a cult object, and its value, as such, leads to a tendency to “keep the artwork out of sight. Certain images of the Madonna remain covered nearly all year round; certain sculptures on medieval cathedrals are not visible to the viewer at ground level.” And so, this piece, as a singular work, is made even more singular, even more intense, by its locale, being both hidden and revered. We can perhaps think of the aura as the work’s spiritual value and its ability to contribute to religious experience, seeing as how Benjamin continually gives examples of religious artifacts. In other words, its aura is its “holiness.”

It’s helpful for me to think of the cult object with the most powerful aura in Judaism: the Ten Commandments, and the room in which it was said would go on to contain them in post-biblical times: aptly “The Holy of Holies.” The Ten Commandments were the physical manifestation of God (in his own handwriting) and God’s greatest gift to the Jews, the Covenant. According to tradition, the Ten Commandments were kept within the Ark of the Covenant, itself kept within the Tabernacle and later deep in the belly of the First and Second Temple. It was accessible only once a year, in a rigorous ritual by the high priest to fulfill the commandment God gave to Aaron, the first high priest, that he must “approach the holy.” Benjamin would describe this as approaching its aura; supercharged to unbearable degrees by being obscured by three layers of inaccessibility and accessed only by this annual act of intensely ritualistic, aesthetic contemplation. Definite, singular, and everlasting. The Holy of Holies is the Aura of Auras.

It’s then helpful for me to think of the diminishment of this spiritual power with a photograph of the actual Ten Commandments published online. In this hypothetical situation, with the Temple still intact but without the tradition of keeping the Holy of Holies secret and reserved, or in Benjamin’s words “with the emancipation of specific artistic practices from the service of ritual,” then the “opportunities for exhibiting their products increase.” And herein lies the depreciation of their aura. Benjamin continues:

“We can readily grasp the social basis of the aura's present decay. It rests on two circumstances, both linked to the increasing emergence of the masses and the growing intensity of their movements. Namely: the desire of the present-day masses to "get closer" to things, and their equally passionate concern for overcoming each thing's uniqueness by assimilating it as a reproduction. Every day the urge grows stronger to get hold of an object at close range in an image, a facsimile, a reproduction. And the reproduction, as offered by illustrated magazines and newsreels, differs unmistakably from the image. Uniqueness and permanence are as closely entwined in the latter as are transitoriness and repeatability in the former. The stripping of the veil from the object [is] the destruction of the aura.”

In the wake of the enlightenment, the aura decay of cult objects into objet d’art, from objects of spiritual religious value to objects of spiritual (though increasingly less so) aesthetic value, is a direct symptom of the devaluation of religious experience in the West. The unveiling of the object is accelerated, argues Benjamin, with the mechanical reproduction of these objects in photography and film, each reproduction taking a bit of the aura of the original work, stripping its uniqueness and transposing it from its locale until something like the Sistine Chapel or the Great Sphinx of Giza lose the intense, holy value that they once held as they are available to contemplate in Vancouver or Cincinnati. And this aura decay has only been accelerated in the decades since Benjamin’s death with the universal proliferation of photographic technology more instantaneous and faithful to its subject than ever.

I’m aware that Benjamin is speaking specifically about the visual arts and not about literature like the Sefer Yetzirah or the Zohar. But I’m equally aware that I may not be treating these works as literature in my mind, rather as Benjamin’s cult objects, and I think this is more common in Judaism than not. Though committing idolatry is, in some mixed-up way, banned by that ultimate cult object, the Ten Commandments, the Jewish practice of my childhood was filled with venerated cult objects, with their own special rules of handling and repercussions of treating them with disrespect. When you organize your library, there’s a Jewish tradition of stacking books in order of holiness, the most holy on top and the least holy on the bottom. A Siddur, a Jewish prayer book, could never touch the ground, and if you dropped it you’d have to give it a little kiss. Dropping a Tanach, a compendium of the Old Testament, would also necessitate a little kiss but there was something a little graver about that. Dropping a Torah meant (though I had only heard rumours of this) that everyone who witnessed the dropping had to fast for 40 days. I’m not sure whether these were sundown-to-sunset fasts, so this slip up, assumedly, meant you that were forced to starve yourself to death. Probably not.

There’s a quasi-mystical significance to this — the language contained within these books transforms their banal container to an object of spiritual magnificence. The aesthetic and substantive value of the language of a book transforms its pages and their binding into an object of holy aesthetic contemplation as powerful as the meaning of the language contained within it. While your repentance for spilling a cup of coffee on someone’s Taschen coffee table book of Rembrandt would be based on ruining something that cost your friend $70, your repentance for ruining a facsimile of a holy text is based on the denigration of an object fueled with an aura from the language within it. Judaism goes so far as to require you to bury a text with God’s name in it when you need to dispose of it, even if it’s a sheet of homework.

Maybe, going even further, a holy book or a scroll can withstand aura decay since its value is from the words that are hidden behind its covers and contained within its pages. And while we can, in an instant, reveal the exact likeness of the Western Wall of the Second Temple, the exact language that is contained in a holy text is hidden until it is received, bit by bit, word by word, by a reader. Hidden even while they are reading it. Language retains its ontological character regardless of its reproduction because its value waits to be revealed until it is met by a reader. Forever hidden in the inner sanctum of its bindings until you, the reader, approach its holiness.

And yet I still feel there are gradations to this. To me, the more hidden or more esoteric a text, the more powerful its spiritual value. That’s why I feel no hesitation in pulling up a web page of the Torah and copying and pasting its first line here:

“בְּרֵאשִׁית בָּרָא אֱלֹהִים אֵת הַשָּׁמַיִם אֵת הָאָרֶץ”

because yes, in some way, I feel freely permitted to reproduce a text that has already been reproduced so many times. I even felt fine deleting a letter.

But I hesitate, and in fact I don’t think I will copy and paste anything from the Sefer Yetzirah or the Zohar, though you’ll find a PDF of either of them with a single Google search. Is it because their aura is too powerful and it prevents me from approaching them? Or am I scared to devalue their aura myself? Or am I, like these Rabbis that placed that initial prohibition, gatekeeping an artifact that I feel can only be approached by those who are worthy? Are these all the same question?

To that last point, it bears mentioning that Benjamin’s treatise transitions into a politics of art as he notes that the invention of photography coincided with the invention of socialism. There is an elitist quality to keeping esoterica esoteric, to keeping the occult occulted. We mustn’t forget that the first book ever printed on a printing press was the Bible, beginning a centuries long de-illuminatory process culminating in the holy word of God available as a free web page that anyone could approach and copy and paste and find some spiritual experience contemplating, negating the necessity of a clerical elite and bestowing spiritual edification to the masses. We also mustn’t forget that the Gutenberg Bible is worth $35 million and is kept behind bulletproof glass. Why value something whose contents can be accessed for free so highly? Why keep it safe at all?

Because the form and matter of a book are enmeshed in an infinite cross-veneration that is indelibly linked to the object’s history; its provenance contributing to its value until it becomes an idol itself, an auto-relic burning a firestorm of its own aura-system, the language sanctifying its pages, the pages keeping valuable its language in an eternal loop of holy-making.

This brings us to our second question: does the power these books that I haven’t read lord over me stem from the language within them? Benjamin helps again here in his dense and profound essay “On Language as Such and On the Language of Man.” But graciously, Benjamin ends the essay with a terrific summary of his complex points:

“The language of an entity is the medium in which its mental being is communicated. The uninterrupted flow of this communication runs through the whole of nature from the lowest forms of existence to man and from man to God. Man communicates himself to God through name, which he gives to nature and (in proper names) to his own kind, and to nature he gives names according to the communication that he receives from her, for the whole of nature, too, is imbued with a nameless, unspoken language, the residue of the creative word of God, which is preserved in man as the cognizing name and above man as the judgement suspended over him. The language of nature is comparable to a secret password that each sentry passes to the next in his own language, but the meaning of the password is the sentry’s language itself. All higher language is a translation of those lower, until in ultimate clarity the word of God unfolds, which is the unity of this movement made up of language.”

To wit: every entity that in some way communicates its “mental being,” be it a human or a squirrel or a lamp, has a language. Human language differs (and appears to us to be the only language) since we are the only entity that names things. We can name a lamp “Lamp” since it communicates itself to us via an ineffable language of things that lack words but nevertheless expresses their mental being. We, in effect, translate a lamps lamp-ness to the name “lamp” based on its communication to us. This isn’t the only translation, however. “If the lamp and the mountain and the fox did not communicate themselves to man, how should he be able to name them? And he names them; he communicates himself by naming them. To whom does he communicate himself?…in the name, the mental being of man communicates itself to God.”

Benjamin proceeds to analyze Genesis 1 from a linguistic standpoint. Benjamin notes in the two creation myths of Genesis that God creates all the elements of the Earth with his own language, and names them (“God said ‘Let There Be Light’ and there was light…God called the light ‘Day’ and the darkness he called ‘Night.”). But in Genesis 2, Man is formed by the hand of God and animated by “the breath of life” breathed into his nostrils and is distinctly not named. The Torah first calls the first man האדם, haAdam, meaning The Man, before dropping the article unceremoniously and calling him simply, Adam. Benjamin sees this as Man naming himself and sees the breath of life as God bestowing man with the gift of a naming-language, after which he finishes the job of creation by translating the things which God did not name in Genesis 1 into the name-language of the divine. Adam’s first job is to name all the creatures of Creation.

Benjamin expands on this notion of ontological translation in the context of art. He sees art as a sort of human-initiated deification process through which we translate name-language back into thing-language and push it further into divine-language: “There is a language of sculpture, of painting, of poetry. Just as the language of poetry is partly, if not solely, founded on the name language of man, it is very conceivable that the language of sculpture or painting is found on certain kinds of thing-languages, that in them we find a translation of the language of things into an infinitely higher language, which may still be of the same sphere.”

I think here we can see the unique perspective of a book. A book is effectively a sculpture, a thing as much as a lamp, and therefore communicates its mental being with an ineffable non-sonic language. But books are also sculptures made up of words, the human name-language, and as such operate in an uncanny liminal space as both a thing and a talisman of names.

There’s a divine quality to books, living in this middle ground. I think that’s why they radiate such a powerful aura for me. “[Man’s task to name things] would be insoluble were not the name-language of man and the nameless one of things related in God and related from the same creative word, which in things become the communications of matter in magic communion, and in man the language of knowledge and name in blissful mind.” This sentiment is doubled, tripled, exploded to cosmic degrees in books that are, like the Zohar and the Sefer Yetzirah in particular, literally fusing the name-language of man and the nameless one of things in an effort to reach to God, in an effort to literally initiate a magic communion.

In a broad sense, this is the goal of all esoterica, and that’s why it is generally disregarded in favour of a more rational theological system and why these books feel like such a strange ontological mirage. Since they thrive on a conceit that the language of their pages is either divinely bestowed and accessed through ecstatic vision or a conduit into the beyond in the form of visions or magical effects, books operate through a distinctly non-rational philosophy. And being made up of words as they are, and since words are supposed to be an exactitude, a singular digit of logic “that by which nothing beyond it is communicated,” these books are bizarre contradictions in that they insinuate so much more that is beyond and promise that beyond in their present-ness. An abstract via the concrete. A periphery via the centre. They are a furthering of Benjamin’s principle that language is “not only a communication of the communicable but also, at the same time, a symbol of the noncommunicable.”

This idea is outlined almost literally by Moses de León, the 13th century Spanish Kabbalist who, at the very least, first publicized the Zohar but often times is said to have written it outright. De León’s exegetical theory of pardes, meaning “garden” in biblical Hebrew, can be thought of as a matrix of meanings possible in each word of Jewish scripture. pardes is an abbreviation of the Hebrew words peshat (surface), remez (hints), derash (inquire), and sod (secret), which I think is a beautiful approach to critical analysis of any subject, regardless of the critic’s level of spiritual investment or religious intent. The four aspects of pardes refer to the four levels in which you can dive into the meaning of a text: its surface level, literal meaning; hints at a deeper, allegorical, symbolic meaning just beyond its literal value; an inquiry into a comparative meaning from similar occurrences throughout scriptures; and a secret, mystic, esoteric meaning discovered through divine revelation or ecstatic vision. With the latter section of this system, we see Kabbalists using the Zohar and the Torah as symbolic grounds from which to delve into dense theosophies, theophanies, and theologies with mythological implications. Systematized here is a method by which to translate name-language into a secret divine beyond-language, an esoteric code hidden between the letters like some quantum field of unknowable proportions, a hidden garden we can descend into via systemic linguistic contemplation.

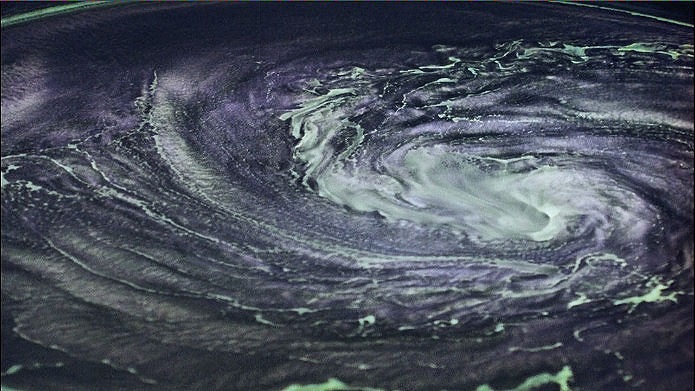

I like to think of Pardes as some sort of quantum epistemology, a sort of infinity of knowledge that continues into the beyond outward and inward, the human intellect sitting in a sort of middle ground of reality, a peshat, a surface, where we can gaze into the possibilities of impossibilities: the non-limits of what once seemed like limits (the fixed quality of words) and the limits of what seemed like non-limits (the human capacity to imagine everything). This leads us back to Tarkovsky, who was endlessly moved by the potentialities of infinity within images and cinema. In contrast to the linguistic infinity that we’ve been speaking of, Tarkovsky saw images as a vessel toward infinity:

“The infinite cannot be made into matter, but it is possible to create an illusion of the infinite: the image…the image makes palpable a unity in which manifold different elements are contiguous and reach over into each other. One may talk of the idea of the image, describe its essence in words. But such description will never be adequate…the idea of infinity cannot be expressed in words or even described, but it can be apprehended through art, which makes infinity tangible.”

And then, perhaps inadvertently inventing a kind of Hermetic theory of art, Tarkovsky pulls this all together:

“If cold, positivistic, scientific cognition of the world is like the ascent of an unending staircase, its artistic counterpoint suggests an endless system of spheres, each one perfect and contained within itself. One may complement or contradict another, but in no circumstances can they cancel each other out; on the contrary, they enrich one another, and accumulate to form an all-embracing sphere that grows out into infinity.”

The influence of art on all other art is an unending field of concentric circles, not moving in binary patterns, but instead in an unpredictable wave of non-rational movements, containing and emanating from each other into a singular image that Tarkovsky calls infinity.

Maybe it would look like this. From Solaris (1972)

I love the idea of the infinity of influence. There’s something beautifully Kabbalistic about it. Contemporary literary criticism’s great master of influence (and, conveniently, its master of Kabbalah) Harold Bloom would agree. In his short book Kabbalah and Criticism, Bloom reads the various Kabbalist systems, being secret revelations of previously established text, as a literalized metaphors of the Torah held concretely by their thinkers, and defines the motive of metaphors as “to be different, to be elsewhere…”

“Let us say,” Bloom continues, “that all religion is apotropaic litany against the dangers of nature, and so is all poetry an apotropaic litany, warding off, defending against death. From our perspective, religion is spilled poetry. Kabbalah seems to me…already poetry, scarcely needing translation into the realms of the aesthetic.” And later, echoing theories he had already set out in The Anxiety of Influence, his book on the relationship between poets and their heroes, he explains that “a poem is a mediating process between itself and a previous poem, but the mediation always belongs to the act of interpreting” and that “to interpret is to revise is to defend against influence….every new poet tries to see his precursor as the demiurge, and seeks to look beyond him to the unknown God, while knowing secretly that to be a strong poet is to be a demiurge.”

This initiates a chain of (sometimes deliberate) misreadings, wherein an influential poem is misinterpreted in the creation of a new one. Tarkovsky’s constantly influencing sphere of infinite art fits right in here as Bloom expands this theory of poetry to a theological zone, noting the massive literary endeavour that the Kabbalists set out on: “confronting, as they did, not only a closed Book, but a vast system of closed commentary, the Kabbalists refused Neo-Aristotelian philosophical reductiveness, refused normative Rabbinicsm with its pious repetition, and took the Gnostic path of expansive inventiveness…” Here is a double movement of tradition and rejection, of influence and revolt, inheritance and disownment.

“‘Influence’ substituting for ‘Tradition’ shows us that we are nurtured by distortion and not by apostolic succession. ‘Influence’ exposes and de-idealizes ‘tradition’ not by appearing as a cunning distortion of ‘tradition’ but by showing us that all ‘tradition’ is indistinguishable from making mistakes about anteriority…I will venture the formula that…strong poets must be mis-read…every strong poet caricatures tradition and every strong poet is then necessarily mis-read by the tradition that he fosters.”

This kind of mystical, spiritual misreading, so frustrating to me in Jewish day school when I’d be confronted with these imaginative commentators and be bewildered at how “made-up” their conclusions felt, is a negation of Benjamin’s aura theory… but not really. They compliment each other. If we read Tarkovsky’s infinite sphere of art as containing not all of human artistic expression but permutations of the same piece of art, and Bloom’s misreading as an imperfect method of appropriation, reproducing Benjamin’s “authentic work,” we arrive at an understanding of the beautiful and haunting instability of esoterica that emerge from its occulted quality, the instability of both the text and the objects that contain the text. An imperfect influence of a text onto its reproduction and a misreading of a text from what it’s trying to reproduce creates a mystic document with infinite permutations that shift and change and only grow in aura throughout history. This is how power grows in obscurity, our third question, via the wrongness that emerges from obscurity.

The imperfect methods by which texts like the Zohar or the Sefer Yetzirah are transmitted (being both birthed in occulted movements and shrouded in secrecy) and thus lacking an urtext, a definite and complete version, each version of the text you can approach feels, in a way, unstable. There is a perpetual “incorrect-ness” to esoterica no matter how critical an edition may seem. Confronting this instability feels bewildering, especially in a genre like religious literature, that usually thrives on its definitiveness and authority. And the blank spaces within something like the Dead Sea Scrolls or the Nag Hammadi remove the ground on which this literature usually stands and casts these texts off into imperfect obscurity, being as they are, through the generation of self-imposed and clerically imposed censorship, obscured. The mechanical reproductions of these texts are wrong, just like what is contained within them feels wrong to our understanding of what religious literature should read like.

Now we’re back to where we began. The obscured ‘wrong’ quality of the actual form and matter of Solaris and the obscured wrong quality of its reproduction on that website precisely mirrors my experience with esoterica. It maintains a powerful aura through its packaging and through its particular way of being. It is made up of a language already beyond the human name-language of exactitude being a film, but further abstracts film language to a stunning spiritual degree. This all contributes to it being wrong, and yet there’s a power within its wrongness. In fact, so many of my most powerful, most moving film experiences have been wrong. I once went to a screening of Apichatpong Weerasethakul’s Uncle Boonmee Who Can Recall His Past Lives (2010) in 35mm which was clearly facilitated by an unexperienced projectionist. A good 20 minutes of the film was projected not only on the screen but mostly on the two walls on either side of me. And in a film of gorgeous, slow throbbing magnitude, feeling it blow up around me in a way that it was not meant to be seen but was corrupted to be, made the film experience so singular, unstable, and intense. I once accidentally watched a shoddily coloured version of Herk Harvey’s Carnival of Souls (1962), and since the film itself is an experiment of capturing that uncanny, untouchable thrumming of bad energy in the air, when those images are debased by some sickly faux technicolour, the bad energy creeps out from the universe of the film into the very texture of the film. I actually did the same on purpose when I watched L’Inferno (1911) which, made 50 years earlier, feels even more uncanny and wrong, reverberating from what has been obscured and the obscurity itself.

The soul of art pulses from its recesses, from hidden corners, from volatile cavities covered in dust so thick it feels like dry soil. I think that the soul of spirituality flourishes here too. At least I’ve found mine hearty and thriving in fertile darkness. It is what’s frightening and fragile about these spaces that make what is discovered here so intoxicating: that threat of it crumbling apart in your fingers as you uncover it. I think that you have to expect it to confound you, you have to know that what grows in murky corridors is inhuman, that these are lifeforms that appear beyond. And so that’s what I expect, what I hope for with the Zohar and the Sefer Yetzirah: that what is contained in them feels like what I hold. And what I hold is heavy and my arms are tired.

- July 28, 2023