Hello. How are you? (Click Email to let me know).

I’m a writer and filmmaker based in Vancouver, BC.

HERE’S MY REEL

On my filmmaker side I make narrative films and music videos. On my writing side I’ve published short stories, essays, and book reviews. I’ve also written novels, feature screenplays, and film theory that are just sitting on my computer as of now but I’d like to publish them too one day. That would be so cool. I love writing.

I’m currently researching and developing a feature film with the support of the Canada Council for the Arts.

You can read essays I’m writing as part of my research here.

I graduated from the University of British Columbia in 2018 with a BFA in Film Production and a Minor in Literature. Since then, I’ve been in VIFF’s Catalyst Program and had my work shown in festivals across the country and my writing published in magazines distributed all over North America. I’m now pursuing my MA in Cinema Studies at UBC.

This is really fun for me and I like doing it. I’m going to keep doing it. Thanks for reading. (Click Email to say you’re welcome).

Contact Me

I See Spirits Rising Out of the Earth

On Hebrew, the Occult, and Movie MagickVancouver still has a vestigial Occult tradition in an area of the city that used to be called Rainbow Road, most of which has been bulldozed over the decades. Once, it had the ambition to be our Haight-Ashbury. It was here that hippie attitudes, acid-test light shows, psychedelia, free-love, and a new influx of spiritual belief systems flourished. I used to live right in the middle of the long dead Rainbow Road — now it’s just called “West 4th Avenue.” Most of those traditions have been gone for a long time. But there’s a clandestine hippie energy that remains in Vancouver, especially in the metaphysical book emporiums and 60-year old vegetarian restaurants of that neighbourhood. There, and throughout the city, interest in the Occult and esoterica still bloom in the right conditions in a way that I never really saw in Toronto. So, it wasn’t until I moved to Vancouver and stumbled upon old pieces of mystic magic and spiritualism in what remains of Rainbow Road that I was drawn to its repeated invocation of the Hebrew alphabet.

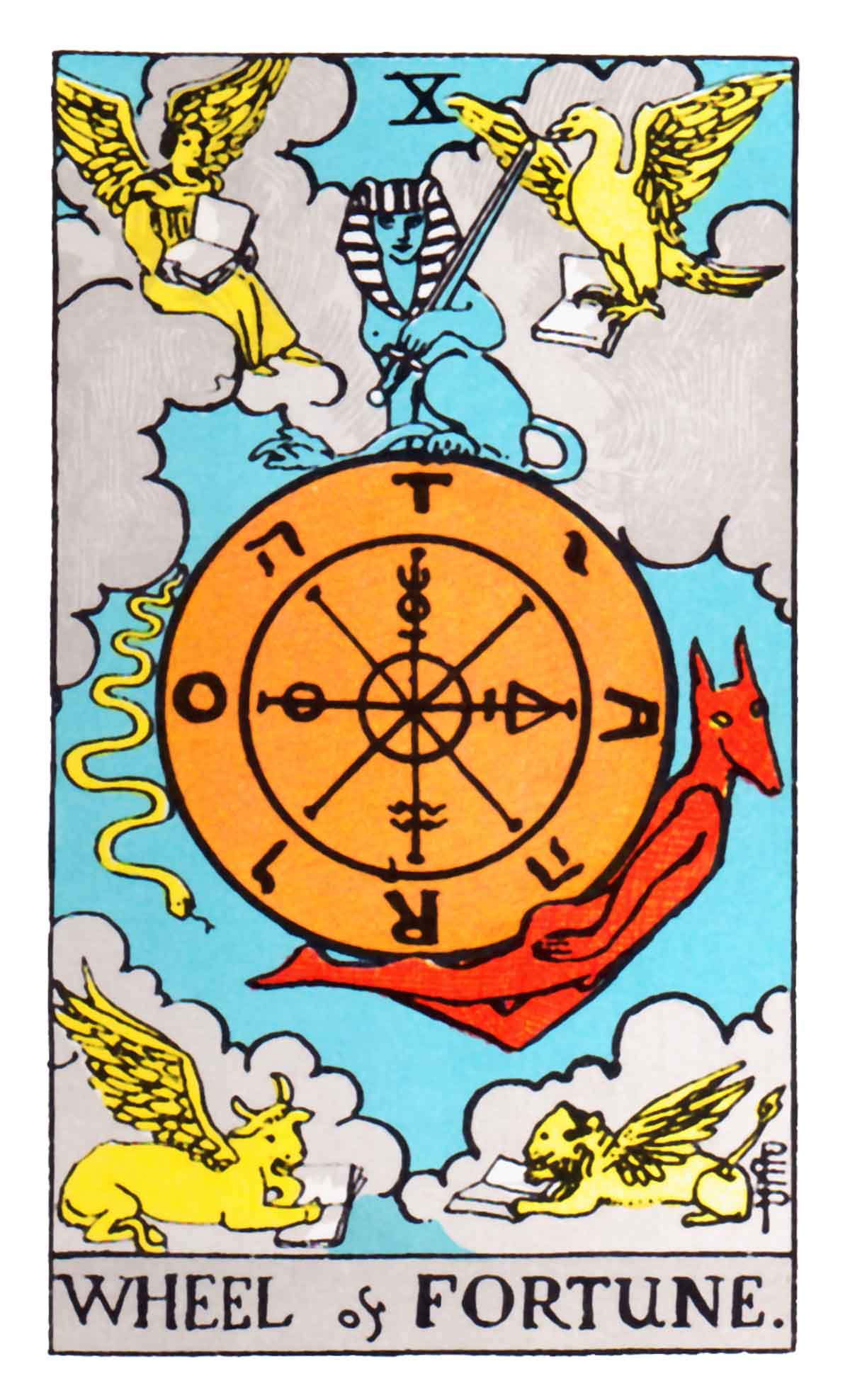

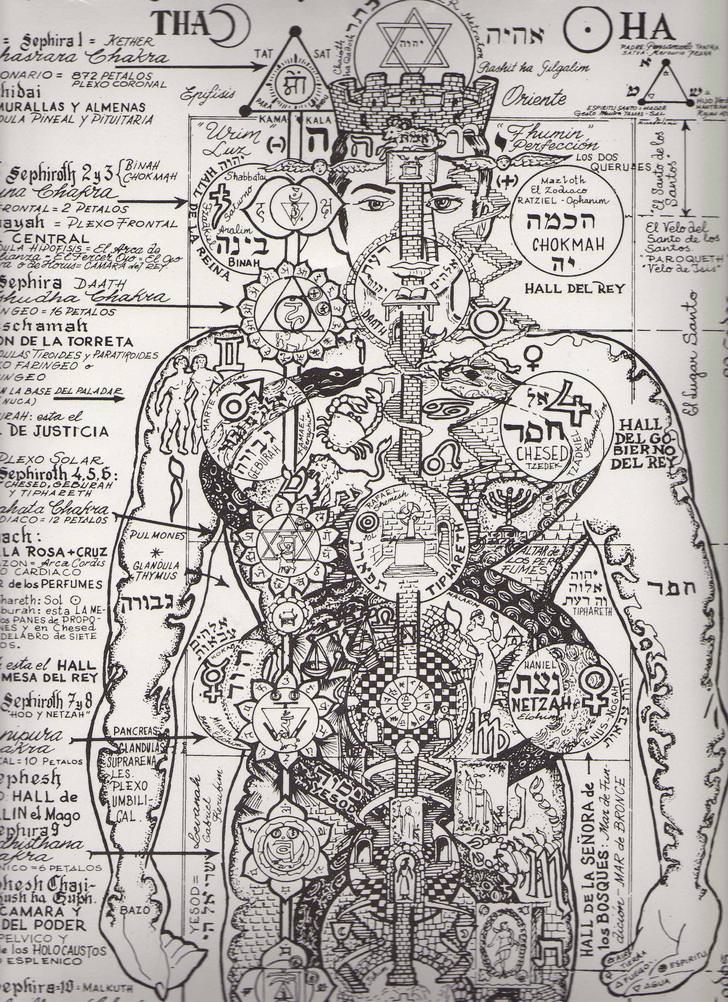

I often stumble upon Hebrew letters, either in the context of a word, or simply emblazoned on their own, either spelling something correctly or printed for posterity, used as some sort of shorthand symbol to indicate a fragment of an Occulted epistemology, a breakthrough vessel into transcendent spheres. Hebrew is repeatedly used in Satanic symbology, Tarot decks, anatomy charts side by side with ancient runes, hieroglyphs, and astrological signs.

Originally, this struck me as kind of funny. I was never particularly good at learning languages, so at this time in my life, seeing the Hebrew alphabet evoked the same feelings as a sine-cosine-tangent table or an “avoir” conjugation chart. It seemed like people were taking something that I thought of as a frustrating but benign element of my childhood learning and elevating it to a communicatory tool with the beyond. But the more I pondered these images, the more they troubled me, fascinated me, and jettisoned my childhood convictions of the banality of Judaism. How could something be boring when, according to so many, it straddles magic, alchemy, and the secrets of reality?

We’ll kick things off with definitions before we head into the murky waters of the dark arts. “Occult” comes from the Latin “occultare” and “occulere,” meaning “secret” or “concealed,” so the knowledge that we approach in these studies is either secret knowledge itself or knowledge meant to uncover the secret truths of the universe, often both at the same time. Contemporary, generalized Occultism eschews specific dogmas in favour of a multiplicity of theological, philosophical, and mystic traditions. Generally, we encounter Pythagorean cosmology, Neoplatonism, Renaissance alchemy, Egyptian Hermeticism, Chinese divination, Tantra, and, most importantly for our purposes, Kabbalah. These interpretory systems are interwoven, and, in their shared truths, purport to uncover hidden corners of our reality that are unavailable to investigators equipped with the popular systems of science, philosophy, and history.

Contemporary American philosopher Eugene Thacker has a terrific chapter on the Occult in his book In the Dust of this Planet, where he points out the hidden knowledge that is uncovered when using this difficult, often contradictory belief system:

“Paradoxically… what is revealed is the ‘hiddenness’ of the world in itself… The hidden world, which reveals nothing other than its hiddenness, is a blank, anonymous world that is indifferent to human knowledge, much less to our all-too-human wants and desires. Hence the hiddenness of the world, in its anonymity and indifference, is a world for which the idea of a theistic providence or the scientific principle of sufficient reason, are both utterly insufficient…Today, in an era almost schizophrenically poised between religious fanaticisms and a mania for scientific hegemony, all that remains is the hiddenness of the world.”

The appeal of Jewish mysticism to the Occult is obvious in this explanation. Instead of revealing literal secrets, Occultic thinkers instead reveal that, beyond the pale of our fragmented knowledge of the universe, one cannot discover truths, they can only reveal things that we can never fathom, things that are perpetually hidden. The ineffability of the Jewish God fits right in here. But, despite Thacker’s positioning of the Occult in a space between or beyond religion and science, it naturally leans to religion. Religious sensations in general are innately predisposed to Occultic knowledge and sensibilities, being, as they are, suppressed or hidden either by their thinkers or the prevailing philosophies of their time. Kabbalah has certainly been subject to this, postured by normative Judaism as a secret, dangerous knowledge that would pickle the brain of any person attempting to read it before they’re ready. This repression, which implies hiddenness, sets the stage for the emergence of sacred sensations and religious sensibilities surrounding Occult.

We can use French philosopher Georges Bataille’s amazing book Erotism: Death and Sensuality to uncover why the Occult evolved into a religious sensibility, pulling its imagery and language from various religious traditions rather than pragmatic scientific exploration.

Bataille looks at repression and taboo and the transgressions thereof in sacred acts and sensations. He sees, in the emergence of taboos around death, that early humans distinguished themselves from animals in two ways: one, via an awareness of mortality, and two, by banding together in communities, delegating tasks, and using tools, or, in other words, inventing “work.” To Bataille, these two facts are interconnected and lead to another distinguishing category: taboos. Burying a corpse was the action taken to enact the first taboo surrounding decomposition and confronting the inevitable mortality of the human body. Taboos were created to combat any violent sensations that may shake a person out of their world of work into the “dizzying” sensations that death reveals.

What death reveals, according to Bataille, is that humans are, at their essence, discontinuous beings. According to Bataille, man “is born alone. He dies alone. Between one being and another there is a gulf, a discontinuity. This gulf exists, for instance, between you and me, and me and you. We are attempting to communicate but no communication between us can abolish our fundamental differences. If you die, it is not my death.” In death, humans transition into continuity, since death is the common thread of all living creatures. Contemplating this continuity is dangerous or, in Bataille’s words, “violent” to the world of work, which depends on discontinuous humans fulfilling their independent tasks to progress the prosperity of a community. “Prohibitions eliminate violence…[that] destroys within us that calm ordering of ideas without which human awareness is inconceivable.”

Taboos are not insurmountable however, and considering that they are absent in animals, not natural. In certain situations, taboos are ritually transgressed to reveal the essential continuity of the universe. “Taboos founded on terror are not only there to be obeyed,” says Bataille. “It is always a temptation to knock down a barrier; the forbidden action takes on a significance it lacks before fear widens the gap between us and invests it with an aura of excitement.”

The taboo-transgression inherent in the very name of the “Occult” charges the movement with religious fervour and fills the act of learning about the Occult with sacred sensations that are innate to ritual transgressions. This is the essence of religious feeling. Bataille goes on to note that all taboos are essentially meant to be violated in controlled and specific moments. He uses human sacrifices as an example: “the victim dies and the spectators share in what his death reveals…the sacredness is the revelation of continuity through the death of a discontinuous being to those who watch it as a solemn right. A violent death disrupts the creatures discontinuity; what remains, what the tense onlookers experience in the succeeding silence, is the continuity of all existence with which the victim is now one.” The Occult has the same ambitions as this ritual sacrifice: to uncover the essential continuity, the truth that thrums throughout and connects the universe. Negative sentiments that normative religion has toward the Occult could be explained as the danger that they feel as inherent in the democratization of the ritual transgression of tabooed knowledge amongst non-initiated clergy, in the violence toward the “world of work,” that religion would evolve to be a part of as it progressed from a spiritual conduit into an institutional authority. The Occult maintained that lens of continuity.

Caravaggio, Sacrifice of Isaac, 1603, Oil on Canvas

Judaism is no stranger to this battle between institutional religion and “violent” factions of mystics. Mystic practices, for much of Jewish history, would be systematically suppressed by Rabbinic authorities. Nevertheless, they survived this abjection and thrived as an occulted epistemology. Jewish mysticism was an unlawful transgression, and we can see it as a rupture bursting out of a people ruled, famously, by laws and taboos that obfuscate the continuity that humanity must periodically contemplate and to which these laws were intended to be gateways. This normative ruling Judaism, so ubiquitous in my upbringing, is the one that taught me the shapes of the Hebrew letters, and so when I first saw instances in the decidedly non-Jewish imagery of witches’ sabbaths and pentagrams, I was mistaken in thinking it was a signal to conservative, rabbinic Judaism, the people of the Book, who cover the spirituality of the continuity of existence in work, law, obligation, and politicking. But the Hebrew letters in an image like this:

instead signals to the mystic ruptures out of the hegemonic rulings of taboos, the intellectual transgressions into an occulted Jewish mythology of the ineffable beyond, ruptures as spontaneous as ecstatic and prophetic visions, thunderbolts from the heavens beyond the world of reason, work, and discontinuity from and into hiddenness.

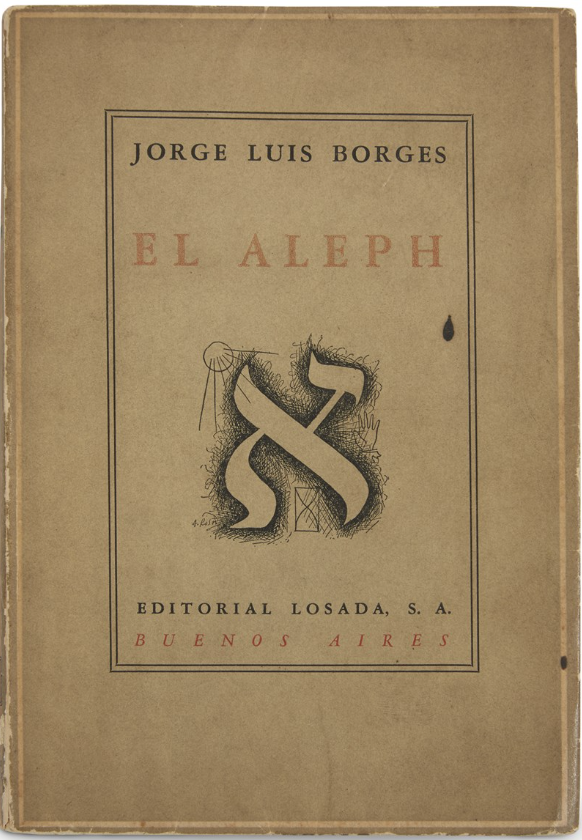

Hebrew letters have been metaphors for ruptures in rationality and instruments to connect with the hidden beyond for non-Jewish mystics, occultists, or simply artists for centuries. A wonderful example of Hebrew as a tool for occult ruptures is in the work of Argentine writer Jorge Luis Borges, who himself was fascinated by Kabbalah throughout his career.

Let’s consider, as the most literal example, Borges’ 1945 short story “The Aleph,” one of my favourites. The title and central object of the book reference the first letter of the Hebrew alphabet: “א” (aleph), whose spiritual and mystic implications in Judaism are profound. The story, from the perspective of a fictionalized Borges, tells of his rivalry with a pretentious poet who is planning to write an epic poem that describes every single location on Earth in excruciating detail. One night, Borges is summoned to the poet’s home. The poet has flown into a panic after finding out that his home may be demolished shortly. The house is key to his epic poem since, underneath the stairs of his diminutive basement, he has found an “Aleph.” An Aleph, he describes, is a point in space that contains all other points. Anyone who gazes into it can see every point in the entire universe from every angle simultaneously, without overlapping, confusion, blurring, or distorting. Borges describes crawling under the stairs, realizing he has trapped himself in the basement of his rival and, fearing murder, calms himself enough to look at the underside of the 19th step. And then…:

“I saw a small iridescent sphere of almost unbearable brilliance. At first I thought it was revolving; then I realized that this movement was an illusion created by the dizzying world it bounded. The Aleph’s diameter was probably little more than an inch, but all space was there, actual and undiminished. Each thing… was infinite things, since I distinctly saw it from every angle of the universe. I saw the teeming sea; I saw daybreak and nightfall; I saw the multitudes of America; I saw a silvery cobweb in the centre of a black pyramid; I saw a splintered labyrinth (it was London); I saw, close up, unending eyes watching themselves in me as in a mirror; I saw all the mirrors on earth and none of them reflected me…I saw bunches of grapes, snow, tobacco, lodes of metal, steam; I saw convex equatorial deserts and each one of their grains of sand…I saw the circulation of my own dark blood… I saw the Aleph from every point and angle, and in the Aleph I saw the earth and in the earth the Aleph and in the Aleph the earth; I saw my own face and my own bowels; I saw your face; and I felt dizzy and wept, for my eyes had seen that secret and conjectured object whose name is common to all men but which no man has looked upon — the unimaginable universe.”

![]()

Borges demonstrates our point here quite literally with that last line, elevating the letter א as a point in which, in his own words, the “ineffable” secrets of the universe can be unveiled from every conceivable angle in a literal tear of the fabric of reality. The tear is hidden and secret from most humans, but in contemplating the Aleph, it ruptures the logic of his reality (and the novel’s reality, puncturing through the fourth wall as he briefly addresses you, the reader). As if the hidden universe is stuffed full of too many secrets, it perforates reality with a window into a vast occulted world. Borges doesn’t even use the term “Aleph” as a covert reference to Judaism. His poet rival specifically calls the Aleph “the microcosm of the alchemists and Kabbalists,” and Borges, in a post-script, elaborates on the purpose of this Hebraic reference. “As is well known, the Aleph is the first letter of the Hebrew alphabet,” he says, “its use for the strange sphere in my story may not be accidental. For the Kabbalah, the latter stands for the En Soph, the pure and boundless godhead; it is also said that it takes the shape of a man pointing to both heaven and earth, in order to show that the lower world is the map and mirror of the higher.” The Aleph in this story can be read as the man that Borges describes, the man in the shape of the actual letter. The Aleph serves as rupturous point that forces humanity to contemplate both the gulf and void between them and universal secrets, as well as their terrifying proximity.

I believe that this short story is key to the power that the Hebrew alphabet holds in non-Jewish mystic images; it’s in fact the very same power it holds in Jewish mystic traditions. Kabbalists, in the tradition of Talmudists, famously pour over the usage, purpose, mathematical, and spiritual implications of every letter of Jewish holy texts, the intimations of their syllables and references, the practical magic that may arise out of their use. They understand that, in the Torah, the world was created through God’s cataclysmic use of language in speech — “Let there be light” — to initiate the creative process. German-Israeli philosopher and historian Gershom Scholem points out that “Language, in its purest form, that is, Hebrew, according to the Kabbalists, reflects the fundamental spiritual nature of the world; in other words, it has a mystical value. Speech reaches God because it comes from God. Man’s common language…reflects the creative language of God. All creation is nothing but an expression of His hidden self that begins and ends by giving itself a name….All that lives is an expression of God’s language.” Instances of what is, according to the Kabbalists, the primordial alphabet of the universe, mystically signal to the deific power of creation and the secrets behind and beyond it. Co-opted Hebrew in occult imagery has the same philosophy.

Creation through mystical manipulation of holy language is a constant fascination of Jewish mysticism, as evidenced in the Golem myth. Golems, whose name means literally shapeless or lifeless manner, are creatures charged with life using combinations of Hebrew letters that either correspond to the name of God (inscribed on the forehead of The Golem of Chelm, incanting “the alphabets of the 221 gates” (according to 11th Century Kabbalist Eleazer of Worms), or writing the word Emet, meaning “Truth” and spelled אמת (The Golem of Prague) on the Golem’s forehead. To kill the Golem, one would simply erase the first letter, Aleph, and reveal the word מת, Mot, meaning death, causing the Golem to crumble apart. Here’s another example of the terrible power of the letter Aleph, Borges notes this story in his Book of Imaginary Being and in his poem “The Golem.”

A still from The Golem: How He Came into the World (1920) Paul Wegener, Carl Boese

The careful assembly and study of the divine properties of language – and the use of it for magical purposes — doesn’t exactly sound like the involuntary rupture that I’ve described up to this point. While we may be able to read historical and contemporary occult movements in the general sense as a rupture of unmet needs at the hands of overly dogmatic and suppressive institutional religion, the Occult is quite famously full of deliberate and sometimes lengthy ritual that initiates said ruptures.

Normative religion, according to Bataille, is no stranger to ritual transgression either. In fact, he argues that ritual transgression is the whole purpose of religion. Even still, it is taken further in the Occult. Maybe because of Occult’s role (and I’m thinking specifically of Satanism here) as an extreme parody of dominant religions, I think that the concept of “ritual” is popularly associated more with the Occult than normative religion. Thacker reads Satanism and witchcraft, with their “black masses” or “witches sabbaths”, as “governed by a structure of opposition and inversion… every element of the black mass, from the blasphemous anti-prayer to the erotic desecration of the host, aims at an exact inversion of the Catholic High Mass.” Today, institutional religion, more often than not, assumes a role as a dogmatic governing body, with excessive law making and law influencing, rather than a channel with which, through ritual, to access humanity’s innate spiritual drive. But ritual has been a mainstay of occult expression, and so popular imagination associates ritualistic spiritual activity with a perhaps sometimes sinister but exclusively spiritual, mystic tradition.

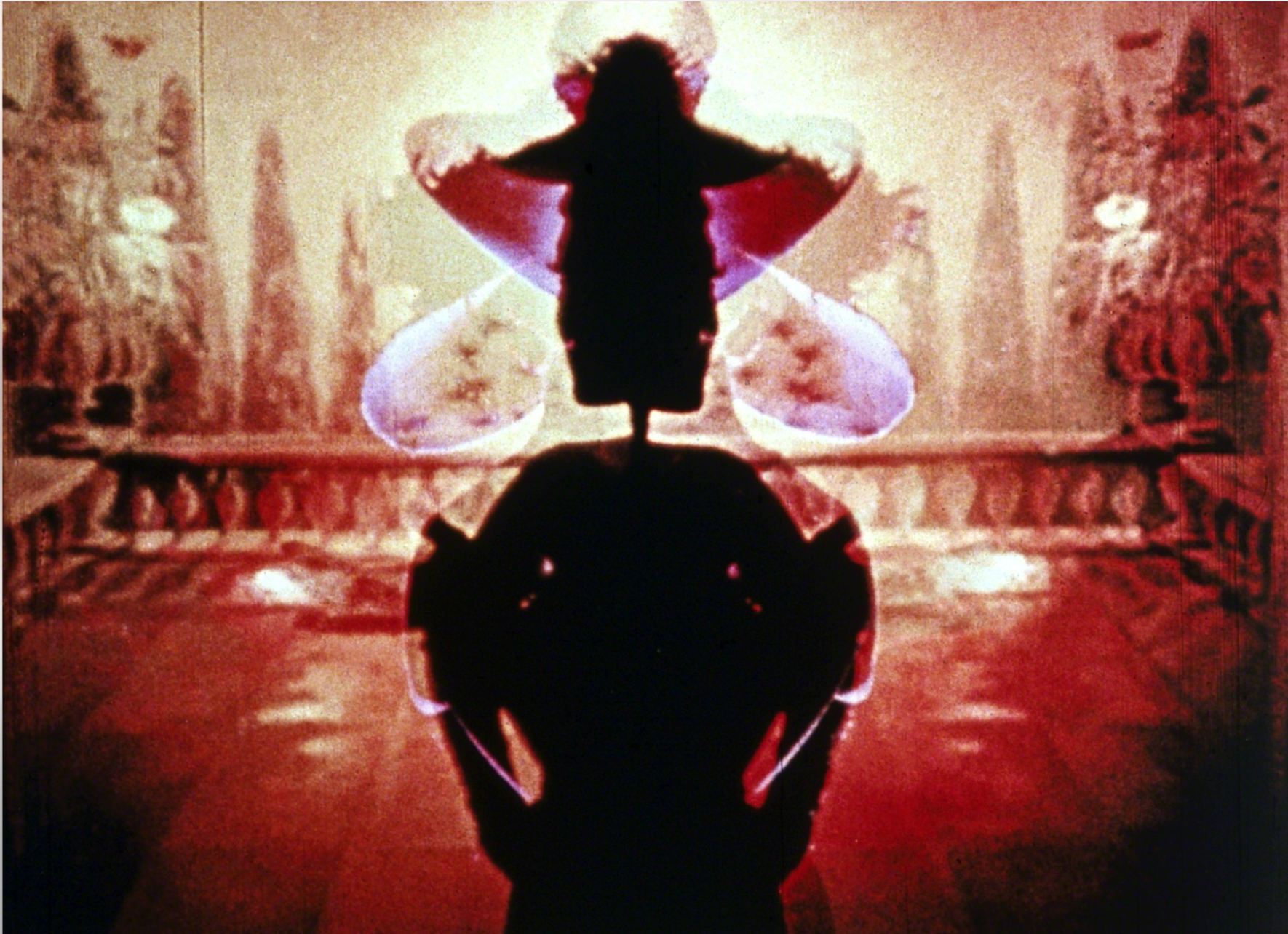

Ritual is a prominent feature in the works of one of the most explicit practitioners of Occultic Cinema, American filmmaker Kenneth Anger. Anger is fascinated by the writings of English occultist Aleister Crowley and is a devout practitioner of Thelema, the religion that Crowley would go on to found (Anger even has “Lucifer” tattooed across his chest). Thelema is a true example of Occult thinking, a conglomeration of imagery from sources as disparate as Egyptian mythology and Yoga. As such, we see in Anger’s work a massive collage of imagery from a mass of mystic traditions, including multiple instances of Hebrew. But the Occult isn’t apparent simply in Anger’s imagery, the very shape of his films shows the influence of Occultic ritual.

Unlike his contemporary practitioners in the early American Avant-Garde cinema scene like Stan Brakhage or Andy Warhol, Anger did not outwardly eschew narrative in favour of formal experimentation. Narrative and characterization are thoroughly present in his work, albeit with an interesting conceit. Most of his films, either those in the occult tradition or those where he sought to explore his sexuality or critique American culture, follow a singular action. Characters prepare for a ritual, enact the ritual, and complete the ritual, at which point the films end. Nothing really goes wrong in a Kenneth Anger film and characters often maintain a muted, pleased expression. Perhaps there’s an unwilling subject in the ritual, as in Scorpio Rising (1964), but as a whole Anger’s work rests on the narrative rhythm of the swirling obligations of rituals, Occultic and otherwise, as the practitioners gather, make their preparations, and witness the resulting magic of whatever hidden power they have summoned.

This rhythm is probably most clear in Lucifer Rising (1972/1980), as we see a gathering of Egyptian gods summoning Lucifer in order to instigate a new age. A mythological goddess watches a volcanic eruption, summons a massive Pharaoh-like figure, who in turn causes a solar eclipse, which awakens a magician (played by Anger), who begins a magic ritual while another figure, painted white, awakens and begins her own ritualistic spell to communicate with the magician, and so on. The ritual is successful, Lucifer arises, and the film ends. No roadblock is encountered, nothing stands in the way of the functioning of this mystic ceremony. Anger sought only to represent the ritual associated with the magic of his Occult tradition. Its steps and procedures are almost akin to a science (here Thacker’s reading of the Occult straddling science plays out fully). This is in the vein of Crowley, who thought of “Magick” (as he called it) as a “science and art of causing change to occur in the conformity with will.” Anger’s work depicts the Occult in the spirit of scientific method and uses cinema as a ritual with which to manifest this magic in reality.

I think that my favourite Anger film is The Inauguration of the Pleasure Dome (1954), which depicts gorgeous, colourful creatures from across half a dozen mythological traditions gathering for a ritual masquerade. As in Lucifer Rising, we watch them slowly, placidly, and calmly prepare. Even when the hyper-kinetic party begins enacting mystic events, the characters maintain their calm demeanour as all that occurs is all that they expected will occur. What I love most about this film though is that, not only does the material reality of these mythologic figures change due to their ritual, but a change occurs for us, the viewers, in a modulation and compounding of the material of the film. Pleasure Dome builds to a magisterial climax of overlays, double exposures, and appropriated footage from spectacular silent films half a century prior. It triggers a collapsing of the film’s reality as well as the reality of the actual substance of the film, transfiguring celluloid into aesthetic chaos. We can perhaps see Anger as not only depicting rituals but as enacting one. Through the process of physical filmmaking, Anger modulates materials and technologies in order to manifest spiritual and physical change. He enacts a ritualistic alchemy.

In an era of predominantly digital filmmaking, the alchemical qualities of film are perhaps not as obvious as they once were, since alchemy refers to a process whose central attention is on materials. This is easier to see in early filmmaking, where the idiosyncrasies of imperfect physical film manipulation are clearer, though no less stunning and powerful. Look at this scene of ritual magic from German director F.W Murnau’s Faust (1926), where our eponymous protagonist summons Mephisto:

In order to represent a metaphysical change in the universe, Murnau enacts a stunning chemical and physical change of the film itself, with stunning overlays of flame, ghost chariots, lightning, and sneaky cuts to signify apparitions. Using the corruptible physicality of film, Murnau makes manifest a corrupted, imagined reality of impossible hidden magic made visible.

In digital cinema, much of these materials are virtual: functional but not physically present. However, cinema still and will always depend on the manipulation of materiality. I may have to beg forgiveness for a lofty proposition, but cinema is innately a ritual act of alchemy in its manipulation of the metaphysical material foundations of reality and time. In the way that a sculptor would use clay or an author language (or a Kabbalist both), cinema uses technology to manipulate time and reality to create new life, a projection of an imagined life into an experiential reality. Filmmakers push time and reality through the prism of their subjective experience and the technology of film and transform it. A new reality arises, often extraordinary and fantastic, and though it is imaginary, it is physically experiential.

Filmmaking is sometimes a punishingly and tediously repetitive and formulaic endeavour. Adhering to screenwriting conventions, courting financiers, applying for funding, getting shooting permits, insurance certificates, equipment forms. And once we get on set, there is a constant rhythm of blocking, lighting, rolling sound, rolling camera, action, tweaking, resetting, moving on, backing up footage, syncing the sound, editing, editing, editing. Instead of seeing this as formulaic, however, perhaps we can see it as ritualistic, a spiritual ritual with innumerable permutations out of which we can manifest shades of imagined realities. I have no doubt that this notion applies to many art forms, and maybe this concept can help us as artists rethink our practices as the spiritual endeavours that they are.

Experimental filmmaker Nathaniel Dorsky speaks of cinema as a mystic, alchemical ritual in his book Devotional Cinema. He stresses the film’s materiality, both illusory and not, as contributing to the physical sensation of a powerful filmgoing experience.

“[In the theatre] we view films in the context of darkness. We sit in darkness and watch an illuminated world, the world of the screen. This situation is a metaphor for the nature of our own vision. In the very process of seeing, our own skull is like a dark theatre and the world we see in front of us is in a sense a screen…Film, insofar as it replicates our experience of vision, presents us with the tools to touch on and elucidate that experience. Viewing a film has tremendous mystical implications; it can be, at its best, a way of approaching and manifesting the ineffable… [unveiling] the transparency of our earthly experience. We are afloat. It is a balance that is neither our vision nor the belief in exterior objectivity; it belongs to no one and, strangely enough, exists nowhere.”

As aspirational as this sounds, I don’t think Dorsky is being unreasonable. A cinema powerful enough to achieve a physical experience, distending and subverting reality, can be a spiritual experience approaching hidden truths (hidden insofar as they are the subjective truths inside the artist).

A film can be an Aleph, a point in which we can see all the hidden angles of the artist’s interior life and how those points intersect with literal and imagined realities. Cinema is then an act of Bataillian transgression, interrupting the world of work and reason to unveil an essential continuity of reality. The movie theatre is an Occultic magic circle with which to summon imagined life. A new set of rules apply in these magic circles as they unveil all that we can never know, the discontinuous subjective reality of humanity. And yet, ironically, in unveiling this hidden truth, discontinuity transforms into continuity. We can, for the length of a film, glimpse into the hidden world of the impossible stirrings of the human heart and the human imagination.

- May 5, 2023