Hello. How are you? (Click Email to let me know).

I’m a writer and filmmaker based in Vancouver, BC.

HERE’S MY REEL

On my filmmaker side I make narrative films and music videos. On my writing side I’ve published short stories, essays, and book reviews. I’ve also written novels, feature screenplays, and film theory that are just sitting on my computer as of now but I’d like to publish them too one day. That would be so cool. I love writing.

I’m currently researching and developing a feature film with the support of the Canada Council for the Arts.

You can read essays I’m writing as part of my research here.

I graduated from the University of British Columbia in 2018 with a BFA in Film Production and a Minor in Literature. Since then, I’ve been in VIFF’s Catalyst Program and had my work shown in festivals across the country and my writing published in magazines distributed all over North America. I’m now pursuing my MA in Cinema Studies at UBC.

This is really fun for me and I like doing it. I’m going to keep doing it. Thanks for reading. (Click Email to say you’re welcome).

Contact Me

The Way Becomes Confused

On the Post-Apocalyptic Road Trip: Humanity, Memory, and RecreationIn 1871, nearly halfway through his brief life, the then sixteen year old French poet Arthur Rimbaud had a revelation. A relentless rebellion staged from childhood onward had alienated Rimbaud from his peers, his family, and his teachers. He made endless attempts to run away from home, had bouts in prison, drank heavily, stole; in general, a complete disregard for etiquette, good behaviour, and social niceties. But he had shown promise as a poet and was tutored classically at the behest of his mother, with a view to developing the young creative’s perhaps only productive outlet, the one quality of Rimbaud’s that wasn’t outright destructive. Herein lay his revelation: to make poetry destructive, to make it annihilatory. To take the one aspect of his person that those in genteel society saw as valuable and raze that value to the ground. To initiate in his soul a personal Apocalypse. Rimbaud was sick of the “subjective poetry” of his tutor, which he thought was “horribly insipid.” He knew that, to be a great poet, which the tutor was not, he had to make himself a seer, a visionary, a witness to the beyond.

That year, Rimbaud wrote to his tutor: “Now I am degrading myself as much as possible. Why? I want to be a poet and I am working to make myself a seer: you will not understand this, and I don’t know how to explain it to you. It is a questioning of reaching the unknown by the derangement of all the senses.” And then, a few days later, he wrote to his friend, explaining that, in gaining knowledge of himself and discovering his soul, he had made his soul “monstrous.” He wanted to “plant and cultivate warts on his face.” In this ascetic, self-obliteration, Rimbaud explained: “The Poet makes himself a seer by a long, rational and immense disordering of all the senses….he consumes all the poisons in himself, to keep only their quintessence… Unspeakable torture…during which he becomes the great patient, the great criminal, the great accursed – and the supreme Knower, among men! – Because he arrives at the unknown!…and when, maddened, he ends up by losing the knowledge of his visions: he has still seen them! Let him die charging among those unutterable, unnamable things!”

We don’t know the details of any particular visions that Rimbaud may have had in his quest to become a seer, a voyeur. But, a few months later, Rimbaud wrote The Drunken Boat, a 100-line poem that we can read from the perspective of his soul un-moored after the auto-Apocalypse that this poetic demiurge let loose on himself, and the resulting “visions” of his Apocalyptic “derangement of the senses.” The poem tells the story of a boat, swamped and flooded with water, drifting out to sea, and is filled with dense, Apocalyptic imagery, perhaps those “unutterable unnamable things” that Rimbaud longed to access beyond the limit of human reasoning.

“I have seen the low sun spotted with mystic horrors,” the boat tells us, “lighting up, with long violet clots… I have seen enormous swamps ferment, fish-traps/Where a whole Leviathan rots in the rushes!/Avalanches of water in the midst of a calm/And the distances cataracting toward the abyss!” The explosion of these painful images overwhelms the boat and leaves it begging for release into the unknown. “O let my keel burst! O let me go into the sea!/ … the black/Cold puddle…”

Rimbaud’s Apocalypse, written in the midst of his self-initiated, spiritual, nearly mystic revolution, meets us where we left off after my essay from June. There, we looked at the function of the Apocalypse as a journey into maximalist symbolism toward a nihilistic limit of understanding in the context of time and duration…and then past it. The end-times as an end to time and a limit to the human capacity to know. What lies beyond is not for us. The Apocalypse is the end of the human. The Drunken Boat, detailing Rimbaud’s revelation of the unknown via sensational derangement, is a journey from our nonsense Apocalypse into our nothing Apocalypse up to the limit of where light stops breaking through the waters of the deep and ends on its descent.

But we can ask ourselves— what does happens when the boat sinks? What lies underneath the murky waters that filled its belly? What happened to Rimbaud-the-Ship after his Apocalypse degraded him into the swampy depths of the ocean?

As to what happened to Rimbaud himself after his violent spiritual purgation, that we can answer easily. After a few torrid, violent years, Rimbaud abandoned poetry, that tool of his massive visionary Apocalypse, and travelled. He walked across Europe, went to Indonesia and wandered the jungle, stowed away back to France, and then left for Cyprus, then Yemen, and then died.

But he didn’t simply travel and live a life far from the obliteration of his creative Armageddon. Rather, he traveled on the basis and as a functioning appendage of human society. That institution that he so hated and against which he had revolted, he finally joined. He gained passage to India as a member of the Dutch Colonial Army and gained a foothold in Yemen as an arms trader. His journey was subsidized and catalyzed by the cruel functioning of European imperialism, the brutal groundwork of its civilization. Albert Camus would decry Rimbaud’s decision to leave his poetic experiment into a life wandering as a “bourgeois trafficker” as “spiritual suicide.” Maybe Camus was correct, but I don’t necessarily see this departure as an end to Rimbaud’s experiment. After the revolution of Rimbaud’s Apocalypse led him into destitution, substance abuse, and near murder, he remedied the terror of the unknown by reinforcing the conventionally human in his work as an adjunct of European imperialism. He led a journey to rediscover society, a journey to again find the Anthropocene. He reinforced the human to escape the hell of the unknown through journey. A journey led him back into the trappings of conventional society, of capitalist dealings, of “civilization.” More than that, Rimbaud recreated that society through the journey. The careful etiquette of European social life that he so disdained as a teenager was rebuilt slowly, in an act of recreation, through this reinforcing trip around the world.

Which Rimbaud do we revere? The mystic Rimbaud who, in an act of abreaction, obliterated literature and kicked off modernism, surrealism, and the act of experiential artistry, in a desperate severance of himself from the “respectable society” into the destitute void of the unknown? Or the Rimbaud that saved himself from complete destruction by enmeshing himself in the problematic human? Should we crave oblivion or crave the continuance of the ills of our modern society? Do we root for Apocalypse? After Apocalypse, do we root to re-establish the human? Or after the Apocalypse, do we just let humanity die?

Personally speaking, I don’t know. But I can see Rimbaud’s experiment reflected in so many other works of “post-Apocalyptic” fiction, wherein humans embark on a road trip in order to find civilization again. In doing so, perhaps they initiate it themselves.

But a brief word on the genre in general. “Post-Apocalypse” is kind of a funny misnomer given our definition of Apocalypse. If the Apocalypse is a limit to the human age, a revelation of the unknown, how has an entire genre emerged around events occurring “post” the Apocalypse? How can there be anything after so strict a limit? In June, we talked about a “nothing” Apocalypse, the nihilistic landscape of non-being inferred by the phrase commonly used in Jewish eschatology, the “end of history,” which the Messiah will usher in. History is the word we use to narrativize time, to humanize time. Ending history means ending all human markers of the world, all human perspectives of those voided markers of the world. It is a universe that has obliterated humanity and what remains is not for us.

So how can we tell any stories of anything after this? When does after even begin? If we cannot witness, know, understand, or even think of a world beyond the human, isn’t “post-Apocalypse” an oxymoron?

I’m inclined to say yes, that there is no “post-Apocalypse” that can really be approached by any narrative, a structure that is innately human, especially one featuring human protagonists. Not one that takes place after a genuine Apocalypse, at least. All these post-Apocalyptic narratives are really nearly post-Apocalyptic narratives.

Rimbaud outlines his method past the unknown in one of his Letters of the Seer. He tells us that it’s up to the poet to “define the quantity of the unknown, awakening in the universal soul in his time:…the measurement of his march toward progress!”

Reading that a little creatively: Rimbaud tells us that the universe, deadened and nullified by the Apocalypse, can be reawakened by the poet’s “time,” by the poet’s understanding of duration. If we substitute “progress” for “duration” and “march” as “journey,” we can see a prototypical acknowledgement of the post-Apocalyptic narrative’s recurring form as a road trip story. To make the unknown known, the poet “defines its quantity,” they give it a limit, they make space for humanity in the post-human by establishing measurement, duration, and movement. Using a linear journey, humans in these stories establish order in order-less chaos, to establish duration in a timeless era.

And now using cinema help us. Perhaps defining the quantity of the unknown means assigning a zone for the unknown. Maybe it’s a little too poetic to use a film with a title like Apocalypse Now (1979) as our key for these questions, but it’s really the title of the source novel, Joseph Conrad’s Heart of Darkness that helps me here. Francis Ford Coppola refers to Apocalypse Now as a journey into the heart of darkness and maybe we can see this as the apophatic darkness of unknowing of which the Apocalypse marks the barrier. And maybe that heart of darkness is a cordoned Apocalypse. Captain Willard’s journey along the “Nung” River, slowly abstracting, surrealizing, growing sparser, reaches its cataclysmic destination toward the end of the film: the temple of Colonel Walter Kurtz, who has proclaimed himself a God and whose followers have proudly graffitied the words “Our Motto: Apocalypse Now!” It’s interesting to read this not as a petition, but as a declaration of fact. This final outpost on the film’s linear journey is a spatial declaration of temporal Apocalypse, a sort of Einsteinian relative “now” where the Apocalypse occurs, in the heart of anarchic, apophatic darkness, and where it threatens to spread. There’s a definite change in the film as Willard approaches this relative Apocalypse. At the outset, there is swirling, conventional war filmmaking, but the logic breaks down the closer we are to reaching the Apocalypse. The film slows and darkens. By the time we arrive at the Kurtz compound, the film halts and gropes glacially through plodding sequences of looking and philosophizing. Willard himself is literally imprisoned for this section of the film. But with the blessing of the imperial United States military, sovereigns of a society of order and policers of the status quo, Willard journeys to this cancerous Apocalyptic now to destroy and reverse. It’s the journey that provides the ammunition to destroy. After the destruction of the Apocalypse, Willard can move again, freely, in reverse.

The road trip, the journey, is a physical act of the human, of narrative, and of memory. A road trip narrative, as we’ll see, mimics the experience of human memory and functions as an emanating beam of human energy through (or in Apocalypse Now’s case toward) a landscape that has abandoned “society,” a trailed blaze in a final act of human colonization, this time into a universe that has shuttered its doors to the human mind.

It seems like films that purport to be “post-Apocalyptic” (though really just nearly post-apocalyptic) often lean toward this narrative, which is linear, robust, and direct, in an effort to offer a stronghold for humanity to survive the unrepentant chaos of nothingness of the Apocalypse and to perhaps rectify the Anthropocene on the other side.

I’m thinking of movies like Death Race 2000 (1975), Waterworld (1995), The Postman (1997) most of the Mad Max movies, Six-Stringed Samurai (1998), Sunshine (2007), The Road (2009), Zombieland (2009), 9 (2009), A Quiet Place Part II (2020), Finch (2021) and plenty of others that feature a human, or band of humans, or band of anthropomorphized non-humans journeying through the ruins of human civilization and the perils and lessons that emerge from it. These movies use a narrative structure that employs forward geographic momentum as an attempt to stretch humanity past the Apocalypse and, with that act, attempt to reverse it.

What makes the road trip such an effective tool? What makes it so distinctly a human form of ammunition against the non-human?

I distinctly remember the day after I watched Apocalypse Now for the first time, a sleepy day late in the winter in Toronto, when the sun didn’t rise until after I got to school. And I found myself feeling haunted that day, shrouded in a languid mood as if I had woken from a nightmare. There are those nightmares that feel so intensely part of your waking life, it's as if they were just especially odd memories — ones corrupted and twisted into miscalculations of reality, but memories nonetheless. But it was the movie that was the nightmare, the memory of the movie, that cast a pall on that day. Obviously, there was the general cynical outlook of the film — but what made it stick so indelibly in my mind? What made it feel like it was a memory of my own?

Aristotle has an answer for us here, noting the singular power of The Odyssey:

“The Odyssey, and likewise the Iliad, [centres] round an action that, in our sense of the word, is one…so the plot, being an imitation of an action, must imitate one action and that a whole, the structural union of the parts being such that, if any one of them is displaced or removed, the whole will be disjointed and disturbed. For a thing whose presence or absence makes no visible difference, is not an organic part of the whole.”

Aristotle is specifically decrying the tendency for Greek poets to include the entirety of their subject’s lives in their Heracleids or Theseids. The Odyssey distinctively tells a single movement, of Odysseus’s journey home. By cutting the superfluous elements of his life, Homer pioneered an experiential manner of narrative that operates via a “unity of action.” It is a singular, fell swoop.

Robert S Duncanson, Land of the Lotus Eaters (1861), Oil on Canvas

The Odyssey isn’t necessarily the first road trip story, but it can serve as a sort of master text for us as we look at the road trip movie. All road trip films, whether or not they are as enormous as Lord of the Rings or as intimate as Easy Rider, belong to the epic in The Odyssey’s conception. We typically begin in medias res and are given a definite destination, far away from our starting point. Point A’s Troy (or really Ogygia) to Point B's Ithaca, Point A’s The Shire to Point B’s Mount Doom, Point A’s Los Angeles to Point B’s New Orleans. On the way, our heroes are driven off course or otherwise corralled into “stations” of sorts, each usually with some kind of master. Polyphemus on the Island of the Cyclopses, Shelob in the Pass of the Spider, a grumpy small-town sheriff in rural Louisiana. After meeting, defeating, recruiting, or in some benign way departing from the station master, our heroes continue on their defined road until the next station, on and on until they reach Point B. Or really Point Z, the road trip a cascading journey of letters on a defined line or ray onward into infinity.

When Homer invokes the Muse at the beginning of The Odyssey, perhaps he’s stretching back further than the nine muses; maybe he’s invoked one of the original, forgotten muses: Mnemosyne, the mother of the muses and Goddess of Memory. I would argue that the road trip, with The Odyssey as its source structure, affects the way the human mind experiences memory, and that Apocalypse Now felt so intense to me the following day because it was an illusory, incepted memory.

The narratives of these films mimic the circuit-like causality loop between time and space, each scene in each film belongs to a different location (station and master), with the actual movement (journey) as an interregnum between two points. Two different scenes are inseparable from the space and time traversed between them, and the film is an experience inseparable from the linear stretch of movement and duration. The piece as a whole, indelibly made up of individual units of space-time that act as a microcosm of the recollection of an individual life.

French Philosopher Henri Bergson, writing on the experience of duration, illustrated its connection to the manner in which people understand time and space. He says that:

“In order to imagine the number 50…we repeat all the numbers starting from unity, and when we have arrived at the fiftieth, we believe we have built up the number in duration and in duration only. And there is no doubt that in this way we have counted moments of duration rather than points in space; but the question is whether we have not counted the moments of duration by means of points in space. It is certainly possible to perceive in time, and in time only, a succession which is nothing but a succession, but not an addition, i.e., a succession which culminates in a sum. For though we reach a sum by taking into account a succession of different terms…it is necessary that each of these terms should remain when we pass to the following, and should wait, so to speak, to be added to the others: how could it wait, if it were nothing but an instant of duration? And where could it wait if we did not localize it in space? We involuntarily fix at a point in space each of the moments which we count, and it is only on this condition that the abstract units come to form a sum…every clear idea of number implies a visual image in space.”

Our instinct is to link duration with space, to link succession with the addition of individual units that have definite space. The road trip movie illustrates an idea which really belongs to every narrative film.

Cinema is a time-based medium (Fiddler on the Roof is three hours and one minute long), and narrative takes place using characters that move through spaces over the course of that run time (e.g., we are in Tevye’s barn at 24 minutes in and at 2 hours and 49 minutes in, the family’s kitchen at 15 minutes, 40 minutes in, and 2 hours and 4 minutes in, the synagogue at 7 minutes in, and 2 hours and 44 minutes in.

The Road Trip movie is an accelerated and exaggerated time-space relationship. A Road Trip movie, with its set runtime (The Wizard of Oz an hour and forty one minutes long) has locations and characters restricted only to specific moments of that runtime (we’re in the wheat field only at 35 minutes in, the woods only at 48 minutes in, and the poppy field only at 55 minutes in). Spaces are inseparable from their point in the duration of the film, never returned to, never taped over, rarely duplicated, fixed at successional points in time forever. Importantly, these spaces exist consecutively to one another, whereas in Fiddler, the spaces are concurrent, in the mish-mashed interweaving spaces of a town, instead of linearly spread across a defined path to the Wizard.

As a tool and as a creative artifact, Road Trip movies, especially in retrospect, are innately experiential, reinforcing the human experience via the human memory, comprised of a litany of actions and environments. In Aristotle’s words, “Since the plot is an imitation of an action, the latter ought to be both unified and complete, and the component events ought to be so firmly compacted that, if any one of them is shifted to another place or removed, the whole is loosened up and dislocated.” The act of our recollection of a single unit of them ignites a recollection of the whole, of the progression of time, experiential in its likeness to the progression of our own lived time. The emotional, thematic, and philosophical change inherent in narrative occurs in step with environmental and temporal change, not sitting atop superfluous environmental movement and requisite temporal change, interwoven and immovable, “firmly compact.” Our recall of the film-watching experience requires us to assimilate a physical journey and a forward, narrative movement through time and space into our own memory, ultimately forming a personal experience. These films aren’t merely a representation of human actions abstracted into fiction. In these pieces of fiction, narrative on its own becomes viscerally human, a reinforcement of human sensations.

Memory as it pertains to space isn’t a novel concept to cinema, it simply makes space more explicit. I read an amazing book this year by Victoria Nelson called The Secret Life of Puppets, where the author charts the evolution of the supernatural in Western culture over the course of a few millennia before it crashed head-first into the Enlightenment, shattering the makeup of the supernatural and sending it underground, into “grottoes” (as she termed it). But, divorced from a society drenched in religion, the supernatural grew grotesque (from the root word grotto) and found its home in fiction, the place of contemporary society’s new religiosity. Within fiction, we continuously explore age-old religious notions of the immortality of the human soul (wherein she looks to possessed puppets or sapient Artificial Intelligence), the beyond and the unknowable (wherein she looks to the unknowable elder gods of American writer H.P. Lovecraft’s pantheon), and, most interestingly for our purposes, the divine memory of the universe present in all its attributes.

In Puppets, Nelson introduces the intriguing concept of psychotopography. In exploring the “madness” of Lovecraft and drawing from a 19th Century memoir from a sufferer of schizophrenia, Nelson notes that “one of the most distinctive features of psychosis is its dynamic of externalization. Madness is experienced as being enacted on the subject from without; a person perceives his own unintegrated psychological contents as outer world creatures and demons who threaten to engulf and physically destroy him.” There’s a subject-object flip here, a collapse of objective reality in the form of the subjective life of the interior human. And “when the inner life of the psyche is allegorized so concretely, the outer world of objects becomes a perfect mirror to view the fragments of one’s projected soul.”

This is an especially popular tendency in 20th Century expressionism, German Expressionist film most obviously, wherein “the environment, whether city or nature, is conceived as the places where subject and object meet…into which the creative self is intuitively projected and whose topographic situation orders and conditions the structure of the poem, novel, play, painting,” or film. It’s more than a pathetic fallacy, wherein the qualities of the environment take on a character’s emotion. Rather, the very shape and aesthetic being of an environment is in concert with a character’s (or an author’s) interior life and infers a greater “transcendent reality.” Nelson refers to the author who projects “interior psychic regions” onto an outer landscape as a “psychotopographer.” Authors of note (not coincidentally, authors that we’ve noted in these essays) are people like Lovecraft, Bruno Shultz as well as works like Samuel Taylor Coleridge’s Rime of the Ancient Mariner and Edgar Allan Poe’s The Narrative of Arthur Gordon Pym. Those last two poems are particularly intriguing for our purposes, since they employ the framing device of the adventurer and their requisite adventure as a journey into the depths of the human psyche, in “travelogue[s] of spiritual journeys” that echo a sort of mini-genre of Hermetic mystic speculation, wherein the geography of the soul reflects the geography of the world, which in turn reflects the geography of all higher worlds, a sort of mystic cartography that tracks the macro and microcosm in the well-worn schema of “as above, so below.” Landscape being both above and inseparable from the human spirit.

But most intriguing to me is Nelson’s evocation of her psychotopographer in the curious history of “memory arts.” Mystics of all religious traditions are not strangers to contemplation as a spiritual act but she notes that, for “Neoplatonists” in particular, “deep thinking was inseparable from the act of remembering — that is, imperfectly recalling the World of Forms. Behind the sense-based memory of the temporal world stands Platonic memory, or anamnesis… All knowledge [according to Plato] is an attempt to remember the blessed and spectacular vision that the living things of the material world imitate in an inferior way from the transcendent world.” Nelson charts the importance of memory prior to the proliferation of literacy, memory being a “preserver of culture and knowledge,” retaining a role, particularly in Greek culture, in mental techniques that orators used to strengthen their memories for lengthy speeches. She sees the psychotopographer in the “method of loci” memory tool:

“The speaker first internalized in his memory a series of real places. These ‘loci’ were usually arranged in a real building possessing a convenient abundance of stories, rooms, corridors, and ornaments. Within this memorized architectural space the speaker placed, in a predetermined order, certain striking visual ‘images’ containing emotional associations, a kind of symbolic code for the sequence of points to be made in the speech…the speaker simply moved through his inner building from location to location in the correct sequence to retrieve the content of his speech as he delivered it…”

As we’ve seen with the Road Trip movie, memory is once again inextricably intertwined with linear journeys through a space. However, the relationship between this technique and practical mystic activities is why I’ve brought us here.

Nelson notes Renaissance Neo-Platonist philosopher Giordano Bruno, who subscribed to the notion that memory recalls the transcendent world of forms in whose images our material world takes shape, and that training your memory transformed it into a “godlike vessel” that could encapsulate the entire universe within a single human mind. There’s a deification process that occurs in the human when they engage in an act of imitatio dei. In Bruno’s complex system of “magic memory,” the participant takes part in a rite wherein they “reflect the whole universe of nature and of man in his mind” and memory becomes “a magic tool for reinforcing the cosmic order.”

Here we can combine our findings. The intensely human experience of the road trip as it pertains to and imitates a memory, and the quasi-deific power of memory in the eyes of the Neo-Platonists, makes the act of a post-Apocalyptic road trip a sort of emanatory ammunition against the decidedly anti-human Apocalypse. It becomes a blast of human something into a wall of nothing as a last-ditch breakout attempt to re-order the universe in favour of the human and to reestablish the Anthropocene. This is a kind of neo-biblical re-creation. The post-Apocalyptic road trip film is a war against God’s plan, using one of the tools of God’s arsenal, Creation, against the final tool in the cosmic narrative, Apocalypse. And so, the journey, a movement across time and space, which are durational units inseparable from each other, becomes a spatial bound, physical, material imitatio dei. Just as God first created a (soon to be human) material world journeying linearly forward across seven clearly defined temporal durational units, humanity endeavours forward in an act of re-creation in journeys across and through clearly defined spatial units that have been planted firmly along a temporal duration, the end of their human-time nigh, capable of a singular action only in the constantly warping shifting ground of film-time.

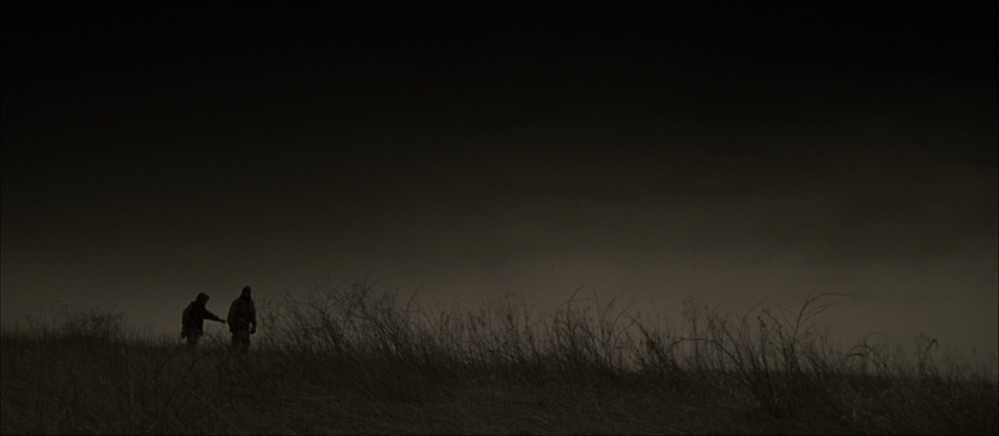

In more literal and physical examples, we can see this voyage take shape in movies that repeatedly apply the trope of a far off, burgeoning new society or otherwise safe-space, free from the undead or disease, toward which we watch our heroes traverse. The utopia to which they head is interchangeably real or a shameless lie in these films, but importantly it’s almost always a newly constructed society, not simply a city that hasn’t fallen to whatever the Apocalypse hath wrought. Films like Damnation Alley (1977), taking us from California to New York and its inverse, Zombieland (2009), taking us from the east to California in a more blatant example of a re-imagined, recreated, colonial, American manifest destiny. 28 Days Later (2002), a more intimate version, takes us from one end of London to the other. Both Mad Max 2 (1981), in a particularly fable-like echoing of this genre’s mythical origins, and Mad Max: Fury Road (2015), in a particularly linear example, transport us to a promised utopia and back again. The Book of Eli (2010) provides an explicit example of the human-god deification theory. And then, of course there’s the film version of the Cormac McCarthy novel The Road (2009), perhaps this theory’s perfect example, in which a father and son journey to a vague safe zone in a post-Apocalyptic United States, during which the father repeatedly encourages his son that they are carriers of “the fire,” a metaphor of their goodness or, in our case, an artifact of the deific qualities of their journey.

The story of Noah’s Ark (in legendary tradition, written far before the Odyssey, in historical tradition, likely 1,000 years after) is another compelling example of this genre’s source texts. On a mission from God, Noah re-establishes humankind on a road trip journey over the drowned bones of a corrupt human society. Rampant with anarchic violence, God decides to flood the world until it again resembles the deep, pre-creation waters before the establishment of humanity. Noah’s task is to organize the animals of the world on his Ark and to establish the new society in top-down, human apexed order in this tale of reestablishing man’s dominion over the animals and establishing the new generative trees of human societies on Earth, this time with order, structure, and reverence toward God. Noah’s story ends with a (later interpreted quite racistly) establishment of a new global societal order when his son Ham “uncovered Noah’s nakedness” in Noah’s drunken stupor. Ham's descendants would be cursed to serve the descendants of his brothers. His brother’s descendants would go on to populate Europe and the Levant, while Ham’s descendants would populate Africa.

Through this source and in these examples we can see that the post-Apocalyptic road trip movie implies a particularly conservative agenda. After society destroying revolutions (brought on either by an overdose of human indulgence through political actions in nuclear war films, spontaneously in zombie films, or unnamed and vague in films like The Road), choice human beings traverse the ruins of a once-thriving nation or world depicted in shots meant to illicit uncanny horror (e.g., Big Ben and Parliament abandoned and destitute, with plastic bag tumbleweeds scattering) in an effort to, using time-honoured, society-building techniques, restart society in the image that it once was. The road trip as a re-establishment of tradition. The film and graphic novel Snowpiercer (2013) offers a more blatantly leftist parody in a double journey from one end of an ark-like train to another, the train itself on its own journey, hurtling through the frozen wastelands of the world to keep its inhabitants alive, with the poor passengers imprisoned at the caboose, and the comically rich passengers enjoying luxuries near the locomotive. In this film, we witness a quasi-Marxist revolution tear through the train to end the capitalist illusion of humanity cobbled together in the wake of the Apocalypse.

This is due a closer, more careful reading by someone better equipped with a political philosophy background than me. I’m a little more interested in post-Apocalyptic road trip movies that approach both genres with unique metaphysical sensibilities, keenly pointing their attention toward the distention of space and time and their relationship to the human in a way that is more in-step with the theological, mystic implications of this mythical road trip that we’ve outlined.

My instinct here was to avoid discussing Stalker (1979) since I feel that I’ve used Andrei Tarkovsky as an example way too much in these essays. But maybe because it’s obvious means that it’s perfect for us, and I really don’t get sick of returning to a film of such gorgeous, delicate power.

Stalker, like Apocalypse Now, is a film of a relative Apocalypse but shifts gears more dramatically as we cross the border into the Apocalypse, aptly titled The Zone. Based on the also aptly titled novel Roadside Picnic, the movie tells the story of a dystopian community bordering a mysterious Zone, a formerly inhabited but now deserted region shrouded in secrecy and strictly guarded by the military. The film follows the Stalker, a man equipped to take people on journeys into the Zone, as he escorts a Professor and a Writer into the heart of this strange landscape. Contained within the Zone, according to some, is a room said to grant the deepest desires of anyone who steps inside. The Stalker believes revealing this room to humanity is an altruistic act and makes a living from shepherding willing pilgrims.

The film’s most obvious striking quality is its shift from sepia to colour about 30 minutes in, which comes after one of my favourite sequences in Tarkovsky’s filmography. The first 30 minutes are quite active, despite Tarkovsky’s requisite uses of long takes. Characters go about their routines, fight, there’s even a quasi-action sequence. But as the Stalker, Professor, and Writer slip past the military on a railroad speeder, we watch silent closeups of their faces steadily for several minutes, the environment whipping past, as they ponder their immediate future, their destinies, with the chugging of the rail car as a cyclic soundtrack in a long, monotonous example of Tarkovsky dilating our experience of time, stretching it and condensing it at once. After this hypnotic, time-sculpting sequence, our senses are flooded with colour as we enter the wild overgrown wilderness of the Zone, various vestiges of human civilization crumbling, giving way to the (quite literally) undulating space. A character notes right away how quiet it is. The Stalker replies “it’s the quietest place on Earth.” Later, after the Writer begins disrespecting the potential dangers of the Zone, the Stalker tells them: “I don’t know what happens here when humans aren’t around. But as soon as humans appear, everything begins to change…the way becomes confused beyond words. This is the Zone. It might seem capricious. But at each moment, it’s as if we construct it according to our state of mind.”

In Stalker, Tarkovsky uses the hypnotic qualities of his particular style of filmic reality corralled into a particular space, a particular path along that space. The three are like human-probes sent into the beyond-human on a doomed mission, since the beyond-human recedes with the presence of the human. Still, they change as well. Their conceptions of the laws of reality warp at the command of this space beyond comprehension, in this zone beyond human time. Not only might they construct it according to their state of mind, their state of mind is constructed by the novel metaphysical laws of this pulsing Apocalyptic space. The beyond, according to the Stalker, is an active, anti-human, metaphysical entity.

In another long, bewildering sequence not long after they enter the Zone. the three wordlessly lie down to sleep amongst the detritus of the forest. As they nod off, the Stalker hears a whispering voice deliver an Apocalyptic prophecy: “and the Sun became dark as sack cloth, and the Moon was like covered with blood...And the stars of the heaven fell to the ground as if a fig-tree… And the sky hid itself, rolled up as a scroll…hills and isles moved from their places…hide us from the face of the One sitting on the throne and from the wrath of the Lamb; for the great day of His wrath is come, and who can withstand it?” The colour changes back to sepia as the camera glides over strange objects just under the surface of the creek, as if evoking Rimbaud’s sunken boat, disintegrating under the corrosive nothing of the Apocalypse in this, one of the most iconic shots of Tarkovsky’s career, cutting back to colour to reveal a black dog laying and watching the group.

Stalker presents the beyond as a radioactive, toxic metaphysics that challenges the laws of the film, the filmic reality, as well as the character’s lives. Who and what can withstand the day of His wrath? No human, including the filmmaker and his camera, enters this Zone, which is devoid of human rationality, without being warped. Not even time itself, nor the quality of light which shrouds the characters in brown and yellow and then blasts them with every colour of the spectrum, can pass through unaffected. The post-Apocalypse sucks it all in like a black hole.

The Room is sort of this promise of a a strengthened humanity, like the outposts of civilization in a zombie film, but again it is a more an abstracted, untouchable kind of superhumanity, a classic wish-granting fabulist deity in a less-abstracted human-to-God transformation (the film revealing the true extent of its power in the final shot). And though the three trudge through various dangers to reach it, they are frozen at the precipice in a sequence even quieter than when they first enter the Zone, as they confront the pollutive qualities of the human, contemplating what exactly will occur if their “deepest desires” could come true. And here, before I spoil anything, the truly destructive reasons for the journey of one character is revealed, tottering between an act of violence against the Apocalypse and an act of violence against the last vestige of humanity altogether.

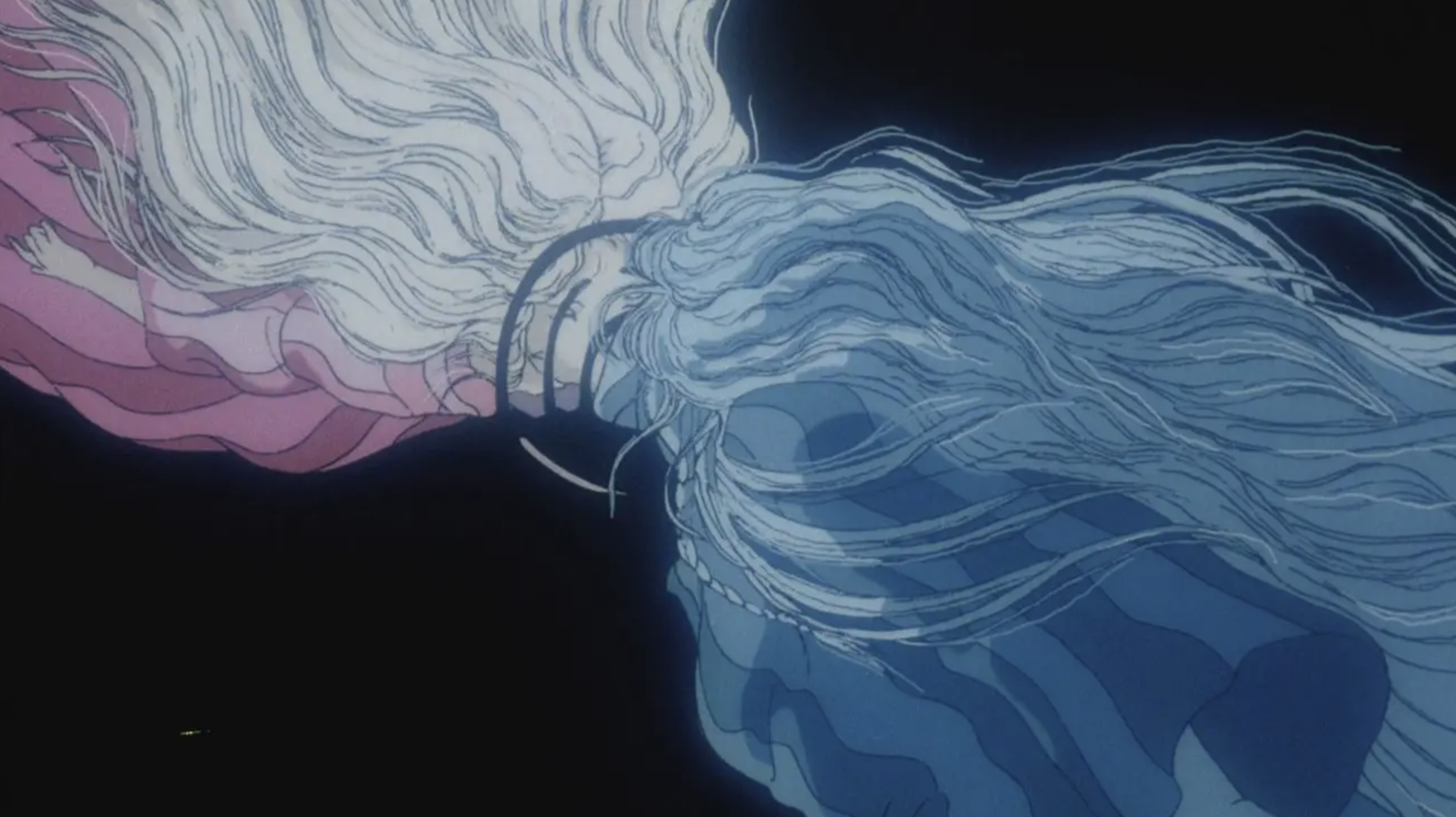

But I think that the perfect film for our purposes is the Neo-biblical Angel’s Egg (1985), an anime film about a young girl carrying a massive egg through a bleak and arid, post-Apocalyptic landscape. She and a soldier that she meets on her journey carry the egg throughout this world and back to the safety of the girl’s home. As we leave the stunning, destitute landscape and approach her home, the soldier tells the story of an alternate Noah’s Ark. One where the ship, like Rimbaud’s, sinks after never again seeing the that dove it sent out. Here, Noah’s mission is very much like the Drunken Ship’s, to construct a final memory of humankind as it drifts out into the nothing of the post-Apocalypse before succumbing to the sucking strength of the unknown.

Here, the soldier highlights our examination of journey and memory. After the surrealistic, winding nature of their trip across the landscape, and after recalling this biblical story of humanity utterly insignificant in the face of the cosmos, he asks: “Maybe you and I… exist only in the memory of a person who is gone. Maybe no one really exists and it is only raining outside.” Confronted with the dwindling remnants of humanity, on a journey with the personification of hope (in the form of an egg, set to hatch new life, the promise of a future), the soldier totters in a dizzying questioning of the reality of everything in the uncertainty of his memory. At the very least, there is the memory of something, some creature greater and more enormous than all of humanity, the beyond-ness to which their journey is subservient.

The soldier’s story and his questioning reveal an alternate God who seems particularly predicated on destroying humanity and, in the shadow of this deity and the skeleton of a massive, true biblical angel, the girl reveals that the real quality of her egg is very much in the image of this new anti-human bible. The boy realizes, like the characters at the end of Stalker, that the egg isn’t the hope of humanity, rather it is the hope of the destruction of humanity. And though he tries to rise above this wrathful God in desperate attempt at deification, he himself is trapped on a sinking boat that rebels against the beyond’s destruction of humanity but which is itself doomed to eventually sink below Rimbaud’s “cold black waters.”

What these metaphysical, post-Apocalyptic road trip films have in common is a tendency for the voyagers to fail at their goal of reversing the Apocalypse and reestablishing humanity. They put forth a rather Lovecraftian idea (and with this, the idea that Lovecraft would plead that he was not a pessimist but in fact a realist) that the universe is indifferent to the trials of man and that the Apocalypse is simply a reinforcement of previously established cosmic order. The man exists several echelons below the prime movers of the cosmos and the purpose of the universe, and the potential to be crushed underfoot of the weird machinations of reality is not only inevitable, its drama pales in magnitude to the universe’s actual purposes. Narrative fails and memory fails because those are concepts that are innately human. And humanity must fail.

Although there is certainly a bleakness to Stalker and Angel’s Egg, I don’t think of these as hopeless films, just films whose philosophy does not imply hope toward the human, be it the fate of humanity or the endurance of humanity’s relationship with itself. They are instead films that have hope in the human-beyond relationship. In a world that is predicated on the brink of a dozen or so Apocalyptic possibilities, the resulting vertigo is enough to inspire the pessimism that Lovecraft swore off at its worst (humankind doesn’t matter) or the realism that Lovecraft professed at best (humankind as we know it is doomed).

I think that road trip films like these ask us to look less at the reality that the vertigo suggests and more toward the vertigo itself. This is the vertigo of someone standing at the brink of a cliff, the cliff at the limit of thought, the limit of humanity, the vertigo of a species that orbits around a black hole. When we approach this limit, we approach the possibility of perhaps not looking into the beyond but feeling it, experiencing the motion of the journey that stretches humanity to the brink of all existence and leaves us spinning beside a place that we were never meant to know. The hollow, resounding echo of a world not for us. With these narratives, we can appreciate our relationship to the beyond (though it’s perhaps one-sided). We can contemplate the blurring spirals that it inspires, the spirals of the dizziness of all humankind, turning behind our own eyelids, as we remember something that was never ours to begin with.

- September 10, 2023