Hello. How are you? (Click Email to let me know).

I’m a writer and filmmaker based in Vancouver, BC.

HERE’S MY REEL

On my filmmaker side I make narrative films and music videos. On my writing side I’ve published short stories, essays, and book reviews. I’ve also written novels, feature screenplays, and film theory that are just sitting on my computer as of now but I’d like to publish them too one day. That would be so cool. I love writing.

I’m currently researching and developing a feature film with the support of the Canada Council for the Arts.

You can read essays I’m writing as part of my research here.

I graduated from the University of British Columbia in 2018 with a BFA in Film Production and a Minor in Literature. Since then, I’ve been in VIFF’s Catalyst Program and had my work shown in festivals across the country and my writing published in magazines distributed all over North America. I’m now pursuing my MA in Cinema Studies at UBC.

This is really fun for me and I like doing it. I’m going to keep doing it. Thanks for reading. (Click Email to say you’re welcome).

Contact Me

This is the Way the World Ends,

This is the Way the World Ends,

This is the Way the World Ends

On Nonsense, Nothing, and the ApocalypseIn 1913, Swiss psychoanalyst Carl Gustav Jung road a train back home to Switzerland. He was, in general, not in a good mood. It had been like this for months, this bleakness, ever since he had felt a definite, gradual darkening of the atmosphere, a vague sense of exposed cynicism, slowly throbbing out from Europe “as though there were something in the air.” The fever would break that day. As the train plunged through the continent, he saw, as he tells it:

“…a monstrous flood covering all the northern and low-lying lands between the North Sea and the Alps. When it came up to Switzerland, I saw that the mountains grew higher and higher to protect our country. I realized that a frightful catastrophe was in progress. I saw the mighty, yellow waves, the floating rubble of civilization, and the drowned bodies of the uncounted thousands. Then the whole sea turned to blood….That winter someone asked me what I thought were the political prospects of the world in the near future. I replied that I had no thoughts on the matter, but that I saw rivers of blood… On August 1, the world war broke out.”

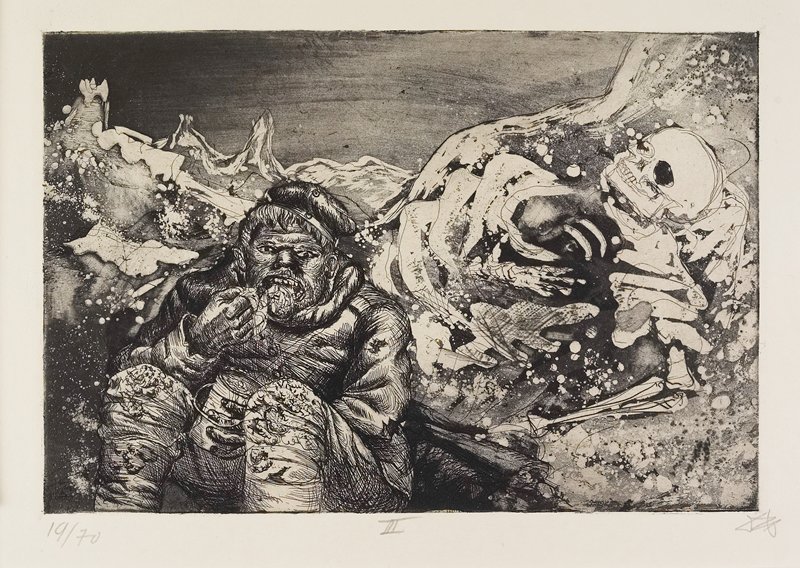

Clockwise from top left: Otto Dix, Mealtime in the Trenches, Disntingrating Trench, Crater Field near Dontrien Lit by Flares, 1924

Naturally horrified, Jung felt torn on how to read this experience. Was this a vision of things to come? Or the natural, albeit corrupted, clockwork of his brain? “I drew the conclusion that they had to do with me, myself, and decided I was menaced by a psychosis.” And yet these things, either visions or hallucinations, would plague him until the outbreak of war, at which point he felt compelled to catalogue this “image,” at the very least, premonition at the very most. Jung describes in his diaries a period of intense and painful confusion confronting the landscape of his dreams, their veracity, and how they could be weighed against a world that believed that one event followed another and that no action could be broadcast into the past, into the minds of special, selected individuals, as visions of horrible bloody poetry, as revelations of the future. Jung, like us, lived in a world governed by a principle of sufficient reason, and yet he was confronted by an experience that defied all reason. This wasn’t just a vision, but the very idea of the end of all things. In the gradient of day to day, no one really thinks the world will change in a sudden, catastrophic bang. Present time flows into new time with the imperceptible flow of mountain rock, not river currents. What was Jung to do, as he joined this grand tradition of visionaries who defied reason and logic and dared to believe that they received a vision of the future, a vision that claimed that the present would end forever?

We’ll start here with Jung, as we consider Judaism’s tension between Aristotelian knowledge based in reason (episteme), Platonic knowledge based in spiritual truths (gnosis), and the eruption of that tension when confronted with notions of the end of the world or, as it is often phrased in Judaism, “the end of history.” Within the body of Judaism, there endures a pained turmoil between expectations and desires of the end-times, a desire to reveal its secrets, be they images or dates, and a desire to suppress or censor or (perhaps more benignly) simply pass over this urge to focus on more pressing matters of theology and law. An urge to put away silly matters like post-biblical prophecy and immerse oneself in questions of the covenant, commandments, and ethical living. One of the earliest Jewish rationalists Judah Ha-Nasi went as far as to say: “if you see one making prophecies about the Messiah, you should know that he deals in witchcraft and has intercourse with demons…for no one knows anything about the coming of the Messiah.”

Ha-Nasi’s sentiments and school of thought on matters of cosmic action persisted through Maimonides and into the Judaism that I grew up with, wherein the concept of Tikkun, which, to some, meant the initiation of the Messianic age and the resulting cataclysmic, cosmic action that would reunify order in the universe according to God’s will, to me simply meant charity, repairing and reunifying the world by making it a better place. This rationalist school of thought has existed since the Second Temple period (597 BC – 70 AD) but is particularly intriguing after the rise of Christianity and in the context of the apocalypse. That complex period saw Christianity’s birth and rise and early, central theological emphasis on Christ’s second coming and final judgement. The rabbinic elite found themselves redacting and suppressing the images that would prove so central to Christianity’s, and therefore the world’s, impression of the apocalypse. The Christians could have the Apocalypse, these Rabbis thought, as they dreaded Messianic speculation within their communities leading their congregations into the growing Christian movement. The Rabbis tried to cut the stalk of apocalypse that thrived and blossomed in early Christianity but the seed was there, and so the magnificent, disturbing, and enduring images that colour Revelations and our contemporary society’s idea of the apocalypse was birthed in Judaism. Those images of destruction remain within us, innate and undying.

Which brings us back to Jung and his notion of the Archetype. Jung’s archetypes are a concept of a universal inherited idea, thought, or image that is instilled in us by the collective unconscious of humanity. Rather than being born as a blank slate, a tabula rasa, Jung theorized that we are born inheriting images and characters that we draw from a reservoir common to all peoples and that these archetypes are activated in particular scenarios, influencing our behaviour and experience. A commonly referenced example is a “mother” archetype activated in a situation in which we are confronted with a crying baby with no one around to help it. According to Jung, our instinct to comfort the baby activates this inherent mother archetype in us. This active quality, the instinct, is a raw primal energy that drives our psychological processes, upon which the archetype, as a symbolic expression and pattern, resides and emerges. These archetypes emerge from the dialectic of an instinct inherited from the collective and from an individual’s own unique instinct, thereby shaping our thoughts and behaviours at the unconscious level.

This psychic energy, which, according to Jung, has throbbed throughout humanity since time immemorial, has famously influenced the common images and characters throughout all mythologies. Look at the primordial flood, for example, in the Torah’s Genesis, the Sumerian Epic of Gilgamesh, the Hindu Manvantara-Sandhya, and the Ojibwe Great Flood, which all emerged independently — or perhaps Jung would argue they emerged inherently linked to one another — in stories of cleansing, retributive deluges at the beginning of time that signified both the end of an era and the dawn of our age.

Jung began developing this theory right around the time he entered into dialogue with his own archetypal image that was inherited from the traditional images of the end of the world. Perhaps this psychic energy was unconsciously charged by innate instincts of a world of geopolitics slowly devolving into war, or perhaps it was mystically bestowed in mediation with a hidden power beyond time, Jung nevertheless engaged with time honoured symbols and imagery of a world enmeshed in floods of blood and masses of corpses.

When I hear the word “apocalypse,” I too am granted visions in the form of archetypical symbols of the same absolute cataclysm and chaos as Jung, which we both no doubt draw from the immense cloud of archetypical cultural images that, consciously, I connect to a Christian influence on popular culture. The chaos of my innate idea of apocalypse has direct lineage to the amalgam of mayhem of the book of Revelations (the direct translation of the Greek apokalypsis). But I don’t only get images of Christian apocalyptic maximalism. I just didn’t know to link the word Messiah with Apocalypse. It wasn’t until recently that I learned of Judaism’s own relationship with apocalypse, using that word as a key, and its own role in the reservoir of the archetype of the apocalypse that coloured the Christian images with which I’m so familiar and in which I found such immense spiritual feeling.

The school of Judaism in which I grew up is an inheritor of the rationalist school of law and ethics, and thus also an inheritor of the redaction of the images that emerged out mystic prophecy/archetypical activation. This exploratory journey back into Judaism that I’m now on is, in some ways, an effort of reclamation of those magnificent and disturbing images that were implied but did not outwardly endure in the stream of Judaism in which I was raised. I’ve embarked, in a sense, on an odyssey into the deep heart of cosmic darkness in Judaism, out of the rationalism of enlightenment and into the surreality of mysticism and its images of profound irrationality and illogic. And so, I hope that Jung’s sentiment on the undying quality of archetypes reigns true. That they, as he says, “are like riverbeds which dry up when the water deserts them, but which it can find again at any time. An archetype is like an old watercourse along which the water of life has flowed for centuries, digging a deep channel for itself.” Certainly, I’ve continuously and unconsciously sought this Jewish archetype of apocalyptic imagery in the media that I love, and my affinity to a particular kind of apocalyptic media leans far closer to what I’ve learned is a more Jewish apocalyptic urge than a Christian one (though nevertheless reliant and inspired by Revelations). Perhaps that has been the desire for a Judaism outside of rational expression, one that feeds on poetic chaos. My portal and my destination into that religious experience has always been the apocalypse as an image of the grandest, most cataclysmic intrusion of nonsense from another world and as a limit to human thought, the precipice of Something before the chasm of Nothing. I yearned for a dashing of sensible, rational, and realist imagery on the rocks of the inane, illogical, and imaginative.

But back to discovering the Jewish apocalypse in me again. The Messiah, Moshiach, that everlasting supernal body of light that burns even in the most conservative of synagogues, is nothing if not a code for the apocalypse, but one, as always, more ambiguous and more ineffable, that explodes out of a non-human beyond of Nothing. German-Israeli philosopher Gershom Scholem explains that there has been a distortion of the history of the Western idea of apocalypse on the part of:

“anti-Jewish interests of Christian scholars as well as the anti-Christian interests of Jewish ones. It was in keeping with the tendencies of the former group to regard Judaism only as the antechamber of Christianity and to see it as moribund once it had brought forth Christianity. Their view led to the conception of a genuine continuation of Messianism via the apocalyptists in the new world of Christianity. But the other group, too, paid tribute to their own prejudices. They were the great Jewish scholars of the nineteenth and early twentieth centuries who, to a great extent, determined the popular image of Judaism. In view of their concept of a purified and rational Judaism, they could only applaud the attempt to eliminate or liquidate apocalypticism from the realm of Judaism. Without regrets, they left the claim of apocalyptic continuity to a Christianity which, to their minds, gained nothing on that account. Historical truth was the price paid for the prejudices of both camps.”

The confusion of what followed from those two camps’ active and passive historical revisionism has resulted in this odd tension in me, these odd, two-headed images of an unknowable, cryptic Jewish Messianic age in a world beyond, and the pervasive Christian spectacle from Revelations. In these essays, I’ve talked a lot about the tension between various factions of Jewish theology and schools of practice but haven’t yet discussed the tension between Jewish imagination and the dominant Christian imagination. Personally speaking, the life of the apocalypse in me is my strongest example of this battle, a constant tug to the brilliant heartbeat of concentric narratives and characters of the Christian apocalypse and the eminent and everlasting cryptic secret of the Jewish Messiah, unspoken and coveted and relentlessly hiding itself from the act of revelation. These are my dualistic archetypes.

Elliot R. Wolfson, in trying to diagnose the shifting images of God in mystic visions, gives a wonderful reading on the role of the infrastructure of cultural tradition on our imaginations and (joining a long tradition) takes Jung to task on his archetype theory:

“A 12th century Franciscan did not envision God as an elderly sage studying Torah, nor did the 13th Century Kabbalist see God as the saviour nailed to the cross. Seeing God like seeing anything is seeing God as something that is under certain aspects that are informed by some prior interpretive framework, the imaging of the divine therefore does not simply result from the mystics’ desire to translate the ineffable experience into a communicable form but is an intrinsic part of the experience itself. That is, for the theistic mystic, the vision is filtered through a religious imagination informed by a nexus of social, cultural and historical realia… The psychic image-symbols are not derived from a Jungian collective unconscious, a common sub-stratum that transcends all differences in culture and consciousness, but rather from the particular tradition of a given mystic. The most basic structural features of the imagining process is that the imagination produces symbols, but the symbols that it produces conform to — indeed are shaped by — specific religious cultural assumptions rather than universal archetypes.

The porous cultural barriers of the 21st Century, compared to that Franciscan’s 12th and that Kabbalist’s 13th, have made it so that, in arguing with Jung, I pull my archetypes not just frk a universal reservoir but from both Jewish and Christian traditions. So, I am repeatedly drawn to apocalypse media that exhibits this tension between the maximalist drama of the Christian apocalypse and the sucking nihilist minimalism of the beyond of the Jewish Messiah. The two images themselves are linked beyond the melting pot of my imagination, they are inextricably descended from one another.

Even if my synagogue’s Messiah was Maimonides’, buried inherent in the Messianic image is the same revolutionary explosion as the Christian last judgement. Jewish Messianism inherently infers catastrophe, cataclysm, and revolution against the pillars of reality, but most importantly it is revolution against the concept of “history.” The dawn of the Messiah isn’t simply, as it’s sometimes interpreted, the continuation of our plane of existence in the light of the redemptive figure of the Messiah; our current world made better, kinder, holier. Instead, it is a revolutionary change and an end of history. The end times are exactly that: the end of time, albeit the end of human time, time being a unit of human organization of reality. Ending history means ending human hegemony over reality, ending the Anthropocene. “History” is a term and unit used to narrativize, order, and organize time, rationalizing duration in the context of human experience, a phenomenology of reality. The Messiah, it is said, will end this way of thinking and obliterate the age of anthropocentrism. Jewish eschatology emerges out of a will to end the “world” as we see it, as a space of human narrative, into a dawning of a “planet” that can only exist outside of human thinking, in that it is wholly connected with and submerged in the divine. In Scholem’s words:

“Messianism is a transcendence breaking in upon history, an intrusion in which history itself perishes, transformed in its ruin because it is struck by a beam of light shining into it from an outside source. The construction of history in which the apocalyptists (as opposed to the Prophets of the Bible) revel have nothing to do with modern conceptions of development or progress, and if there is anything which, in the view of these seers, history deserves, it can only be to perish. The apocalyptists have always cherished a pessimistic view of the world. Their optimism, their hope, is not directed to what history will bring forth, but to that which will arise in its ruin, free at last and undisguised.”

What will arise we will never truly know. Because what begins is an age where human conception ends, a world not for us (though one, according to various eschatological or messianic sects in Jewish history, we will help bring out through actions that will “push for the end” or accelerate the coming of the Messiah).

This “nothingness” of the apocalypse harkens back to a concept that I’ve repeatedly turned to, Judaism’s relationship with “negative theology.” Far from being unique to Judaism, negative or apophatic theology refers to an idea of God that, since God is not human, cannot be understood by humans and thus can only be described in negative terms, in things that it is not. It perhaps found its first blatant expression in the Neoplatonic movement in and around 200 AD. Neoplatonism espoused a theology surrounding a divine entity it called “the One,” a simple, ineffable entity that is the creative source of the Universe and out of which all things emanate. This divine source is impossible to describe or locate, since it is not only the source of all beings but surpasses all beings. Language begins to lose its ground in the face of something so beyond reality and human imagination. We enter a dark chasm of unknowing. To quote an early Neoplatonist Christian, Dionysus the Areopagite: “the fact is that the more we take flight upward, the more our words are confined to the ideas we are capable of forming; so that now as we plunge into that darkness which is beyond intellect, we shall find ourselves not simply running short of words but actually speechless and unknowing.” A being beyond beings is utterly ungraspable by language and therefore incomprehensible in symbols.

Gustav Dore, Paradiso, Canto 34, Engraving, 1868

In the Jewish apocalypse, this darkness, this entity of unknowable proportions becomes reunified and overtakes the anthropocentric direction of the world. It becomes the world. By reunifying, the world becomes one: the One. Imagining this causes the apocalyptist’s cognition to buckle in on itself and perhaps this is the reason for the increasingly strange and enigmatic language of the Jewish apocalypses. Scholem confirms: “Knowledge of the Messianic end, where it oversteps the prophetic framework of the biblical text, metamorphosizes into an esoteric form of knowing… There is something disturbing in this transcendence of the prophetic wish which, at the same time, carries along with it a narrowing of its realm of influence… the stronger the loss of historical reality in Judaism…the more intensive became the consciousness of the cryptic character and mystery of the Messianic message.”

Scholem is specifically describing Messianism around the destruction of the Second Temple but the phrase “loss of historical reality,” referring to trauma is particularly poignant in regard to Jewish Eschatology’s enduring apophaticism. Instead of the cataclysm of the Messiah, the Jews were subjected to the trauma of destruction, death, and expulsion and, in the void of the rupture of human trauma, began expressing themselves in pleas to a world after this world in which human action has no significance in the context of a reality belonging to something so completely unhuman. The loss of history at the hands of the Romans echoed the loss of history at the hands of the Messiah, though the former is destructive and the latter redemptive, resulting in prose stylings of cryptic, bizarre, and sometimes nonsense imagery, and occasionally imagery signalling an apophasis of nothing, darkness, and black.

When it comes to artistic representations of the apocalypse, artists must ask themselves: “can we comprehend something beyond comprehension? Can we experience an experience without time?” The resulting art is, in my view, as exciting and enormous as the cataclysm of apocalypse as it approaches the very limits of human thought, expression, and experience, the very moments before the end of human comprehension and human time. Sometimes endeavouring to apprehend the moments after. For our purposes, I think we can divide the art of the apocalypse into two streams: a Nonsense Apocalypse and a Nothing Apocalypse, each harkening toward an end of history as an end to the Anthropocene as an end to the human conception of the universe as an end to rationality. One school favours a discombobulating madness as an attack on comprehension, the other favours an a kind of sensory deprivation as a tool to attack the experience of duration.

Let’s look at two pieces of art that seek to depict a non-human universe before we move to two films that seek to imagine that universe and render it experiential.

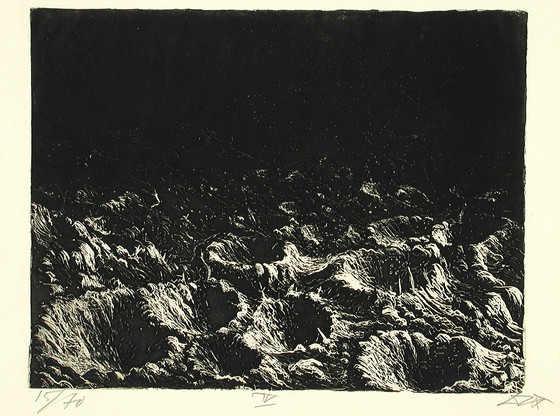

Here we have Hieronymous Bosch’s The Last Judgement (c.1482) and the black page in Robert Fludd’s The History of the Physical and Metaphysical Cosmos (c. 1671). The difference between Bosch’s famous maximalism and Fludd’s striking minimalism is obvious, but the depths of their different sensibilities are profound.

Look beyond the tableau of colour and shape and the details of Bosch’s feverish mad dream. An inventory of all the figures reveals a mess of the ridiculous, an abject burst from the mouth of madness. A dancing black spherical monster is playing a trumpet formed out of the hollow bones of its own face, curling back on itself with a snakelike neck while, behind him on a red platform, a naked man is seduced by shadowy lizards writhing underneath him. A giant head walks with the feet of a cockatiel, below him a dragon woman churns a body in a bloody mill, a small boy shits stinking water out of his ass, which is collected in a rotten keg by a man walking in flayed and stinging red flesh, and this now crimson liquid is drunk by a man seizing with vomit. Bodies that are now only flesh are strung up and gawked at over an open flame. A man is tied up as an enormous black tapeworm crawls up his body, impaled head to crotch on an enormous stake. A corpse of an old woman, blue and bloated with the rot of recent death, pours oil over a man whose muscles are cramped by pain. Next to her, a man is cooked in an enormous pan and his body is folded in on itself and melting. If this vision is terrifying, it is rendered as such by the collage of images of near incomprehensibility.

Bosch’s vision of a collapsing Anthropocene has always felt to me to be several centuries in anticipation of Surrealism, presenting Earth as an exquisite corpse, reality distorted and improvised until the world is made up of bodies of nonsense. This is a sur-reality, a new reality cast violently on top of our reality in a catastrophic injection of logic from a realm beyond logic. 450 years after Bosch, French writer André Breton would explain in the Surrealist Manifesto that his movement was “psychic automatism in its pure state, by which one proposes to express…the actual functioning of thought. Dictated by thought, in the absence of any control exercised by reason.” Surrealism emphasizes pure release in order for an artist to examine the base functioning of their unconscious brain, regardless of whether it appears as nonsense. We can see this as an opening of the reservoir of Jung’s archetypes and an outpouring of images outside of their contexts, crushing images that exist in accord to logic underfoot. In Bosch’s magnificent mishmash of images, he depicts a humanity broken under the weight of a reality that operates “in the absence of any control exercised by [Human] reason,” a cataclysmic event wherein humanity submits to a reasonless dimension invading our own, Scholem’s “intrusion of transcendence.” Like the unconscious, the divine realm is a hidden source of imaginative power, a well of power that supposedly imagined and created our own realm. Bosch’s Surrealist Apocalypse gets its power from the will of logic (our reality) yielding to the will of illogic (a divine reality) in a catastrophic injection of nonsense imagery from a sphere of reality that was once enshrouded and is now revealed. Pun intended.

The one shred of logic that remains in Bosch’s piece is the logic of time. Despite the chaos, we see a definite duration in the three panels of the piece. Moving from left to right, we see The Garden of Eden wherein virtuous angels fight rebel angels, who turn into devils as they fall above Adam and Eve committing the original sin, the explosion of the last judgement proper from the Book of Revelations, and Hell itself where the damned souls, having since been judged, are received by Satan. Within the main centre panel itself, the logic of time remains as well. There is a definite degree of blurring and obfuscation as the planes of reality recede from the foreground until they are covered in blurry shadows, emulating the fog of the past.

In writing on the use of deep focus (eliminating the usual blurry nature of further fields of space in photography), French philosopher Gilles Deleuze noted that depth of field is a “function of remembering, that is, a figure of temporalization.” When someone like Orson Welles uses radically deep focus in filmmaking, he accentuates the “sheets of pure past…and contracts the actual present. Depth of field will go from one to the other, from extreme contraction to large sheets and vice versa. Welles deforms space and time simultaneously; dilating and contracting them in turn…[causing a] disturbance of its constitution.” Bosch does not, retaining the constitution of time as sharp and identifiable in the present (the foreground) and blurry and undefined in the past (the background). The Last Judgment is a painting that is filled with duration and therefore is distinctly pre-Jewish apocalypse. French philosopher Henri Bergson, that definitive philosopher of time, defined duration as “the flow of the real, the ceaseless creative unfolding of the universe” and “the lived experience of time, the subjective sense of the past, present, and future intertwined in the fabric of our consciousness.” Time is the lifeblood of creation, humanity, and humanity’s universe. The real end of the world begins when duration has no meaning.

We find that end of the world in Fludd. His piece depicts a world without time by depicting nothing at all, Nothing in all of its profundity. His piece appears in his comprehensive Hermetic atlas and history of the universe, which is filled with other illustrations and diagrams. With this page. he attempted to depict the world outside of creation and decided to use a sublime and declarative black to depict this universe surrounded on all sides by the words “Et sic in infinitum,” “And so on to infinity…” American philosopher Eugene Thacker looks at this choice as more intensive then simply colouring a page black. “Fludd had the intuition that only a self-negating form of representation would be able to suggest the nothingness prior to all existence, an un-creation prior to all creation. And so, we get a ‘colour’ that is not really a colour – a colour that either negates or consumes all colours. And we get a square that is not really a square, a box meant to indicate boundlessness… this simple little image requires a lot of work on the part of the viewer, perhaps as much work as in Fludd's other, more complex diagrams.” Perhaps even more work than The Last Judgement, as this piece requires balancing our concepts of Nothing and Being.

Heidegger’s answer to Fludd’s piece would be to “ask about the nothing. What is nothing? Our first approach to this question has something unusual about it. In our asking, we posit the nothing in advance as something that “is” such and such; we posit it as a being. But that is exactly what it is distinguished from. Interrogating the nothing — asking what and how it, the nothing, is — turns what is interrogated into its opposite. The question deprives itself of its own object.” It deprives the question of its subject as well, as we have no place in the nothing. This is not a black void that we as humanity float in, which would negate its voidness. This is the universe of no thing, and as soon as we try to comprehend it, we lose our ground as we can only comprehend it from our perspective. We have no perspective. There is no human. We have to adopt the perspective of non-perspective, the lens of the void, the vision of every plane of the universe as the colour that is no colours. Seeing the world as effectively as we can see out of our own foot. A vision of nothing, no vision at all. Black is the absence of any degree of the visible spectrum and therefore we cannot even see it. And so, if we are seeing it, we are not seeing it with human eyes. In this universe outside of our reality, we are buried under a mountain of non-being.

So this is decidedly the non-human universe that an “end of history” and an end of human markers of characterizations of the world would look like, a boundless void “on to infinity,” negating time. A deep focus lens into nothingness. This piece is an apocalypse of abnegation, superseding an apocalypse of chaos by rendering all factors of that chaos as subordinate to the void. Maybe we can see Fludd as sequential to Bosch, Bosch as the moments before the death of humanity, Fludd as the unknowable after. Bosch as the moments before the end of history and the final dregs of duration, Fludd as the universe where duration has no meaning and time falls before infinity.

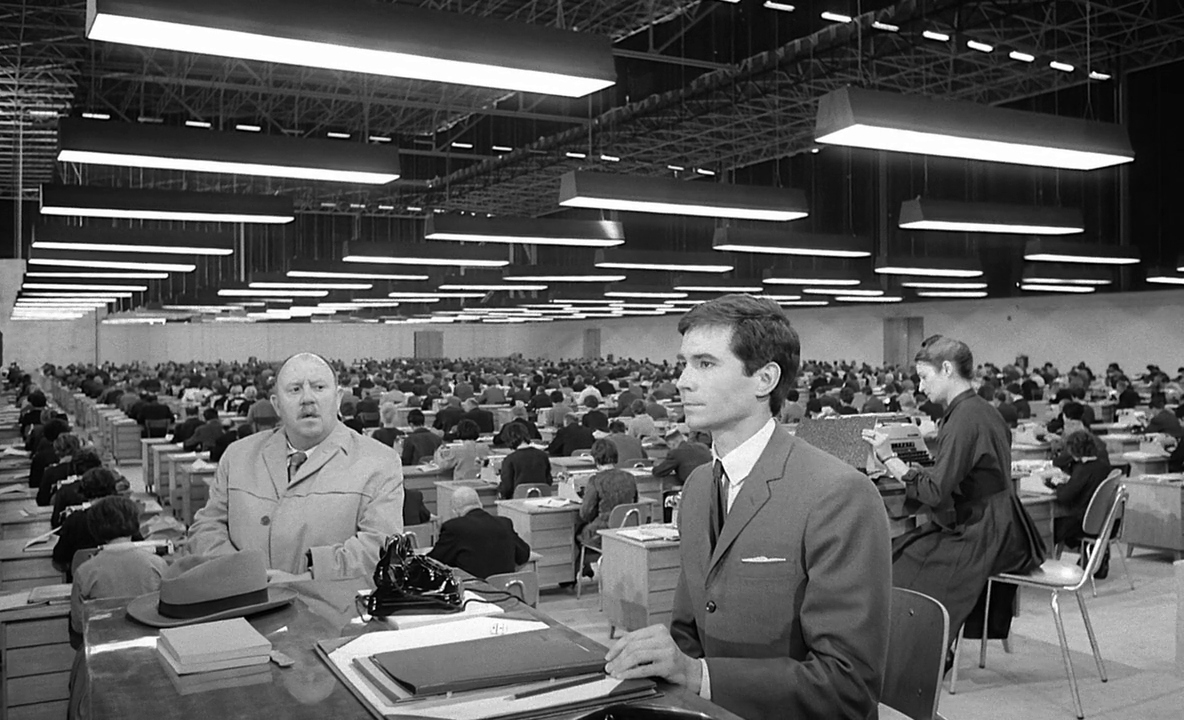

For an equally powerful cinematic rearing of time, there’s no one better to look to than Andrei Tarkovsky, the Russian filmmaker who repeatedly turned to the apocalyptic and post-apocalyptic in his career-long question to the nature of time. In his magisterial final film The Sacrifice (1986), one of my very favourite movies of all time, we see Tarkovsky make several measured assaults on the human understanding of duration. The film tells the story of a group of friends who live on a Swedish island in the far north, as they grapple with the outset of World War III and a nuclear holocaust, of which they only have knowledge through the sound of distant fighter jets and news reports. They are too remote to see any of the carnage or feel any of the bombs, and yet the low-hanging poisonous ennui erupts their lives. In a heart wrenching scene, we watch quietly as one of them sobs desperately and the rest listlessly move throughout their eerily sparse house. They are punished by an invisible Apocalypse, an apocalypse, like Fludd’s illustration, of nothing. What follows is a cinematic experience of a Nothing Apocalypse via a distension, and renunciation, of duration.

Tarkovsky cleverly sets the film near the Arctic Circle, so we are never witness to a setting sun, despite watching the characters sleep. We have no visual indication of the passage of time. Tarkovsky also halts a traditional forward impulse of narrative film, depriving us of a natural sequence of events. Rather, the film is made up of conversations that blend and engulf one another, many taking place over the course of a single shot, much of the film taking place squarely in “real time.” His use of long takes in this film in particular is effective to the end of denying duration. By eliminating cutting, Tarkovsky likewise eliminates emotional checkpoints within a scene, moments which signify release and perspective. The camera is adrift in its perspective, slowly moving over the course of several minutes from one wide shot of great magnitude to another of equal magnitude, and cutting to another long shot of enormous wides. Our brains, so conditioned to being directed in a linear path along scenes by dramatic beats, are deprived of that forward movement in a quiet, unending drift through the trauma of apocalyptic assuredness.

By depriving the audience of these conventional cinematic signifiers of duration, and of the physical and metaphysical laws of the diegesis, we reach an altered state of cinematic perception wherein we ‘lose track of time.’ Through a distension of our conception of chronology and duration, we enter a state of near timelessness, completely thrown off a traditional, linear extrapolation of causes and their effects, of events and their consequences. We are now part of an experiment taking place almost beyond time, while watching a medium that is inherently entangled with time. Tarkovsky famously called filmmaking an act of ‘Sculpting in Time,’ and emphasized the plasticity of time as unique to an artist’s own perspective of the universe. In this film, which depicts the beginning of the end of the human world, he fully realizes his theory that: “Cinema is a time art. Its power lies in its ability to capture and manipulate time, to extend or compress it, and to create a unique experience of duration.”

In Deleuze’s theory of cinematic “crystal-images,” where he reads into the “circuits” between virtual images (reflections, photos, film, etc.) and actual images (the source of the virtual image in reality), he speaks to a radical, new understanding of past and present and their tendency to collapse:

“We can always say that [the present] becomes past when it no longer is, when a new present replaces it. But this is meaningless. It is clearly necessary for it to pass on for the new present to arrive, and it is clearly necessary for it to pass at the same time as it is present, at the moment that it is the present. Thus, the image has to be present and past, still present and already past, at one and at the same time…the past does not follow the present that is no longer, it coexists with the present it was. The present is the actual image and its contemporaneous past is the virtual image…déjà-vu or already having been there simply makes this obvious point perceptible: there is a recollection of the present, contemporaneous with the present itself.”

The present duplicates itself at once into “perception and recollection”, constantly appearing and diverging. This confusion of chronology results in almost a hypertext that halts the experience of duration. “Time has split itself in two,” Deleuze says, “at each moment as present and past, which differ from each other in nature…it has split the present in two heterogenous directions, one of which is launched towards the future while the other falls into the past.” The Sacrifice’s narrative of bleak and beautiful drama and images of staggering beauty allow us to interact with the film as a visceral experience’ in this viscerality, we see the illusion of the film being an “actual” image. The film then holds us at a surrealistic arm’s length with its denial of mythology, leading us to meet it as a “virtual” image. Tarkovsky’s film is a “crystal-image,” as defined by Deleuze, scrambling our conceptions of linear time akin to a déjà-vu, constantly repeating itself, to use Deleuze’s metaphor. It is “a point of indiscernibility of the two distinct images, the actual and the virtual, while what we see in the crystal is time itself, a bit of time in the pure state, the very distinction between the two images which keeps on reconstituting itself.” The experience of this time-crystal makes this indiscernibility discernible; The Sacrifice is a tactile microcosm of the time crystal confined to its runtime.

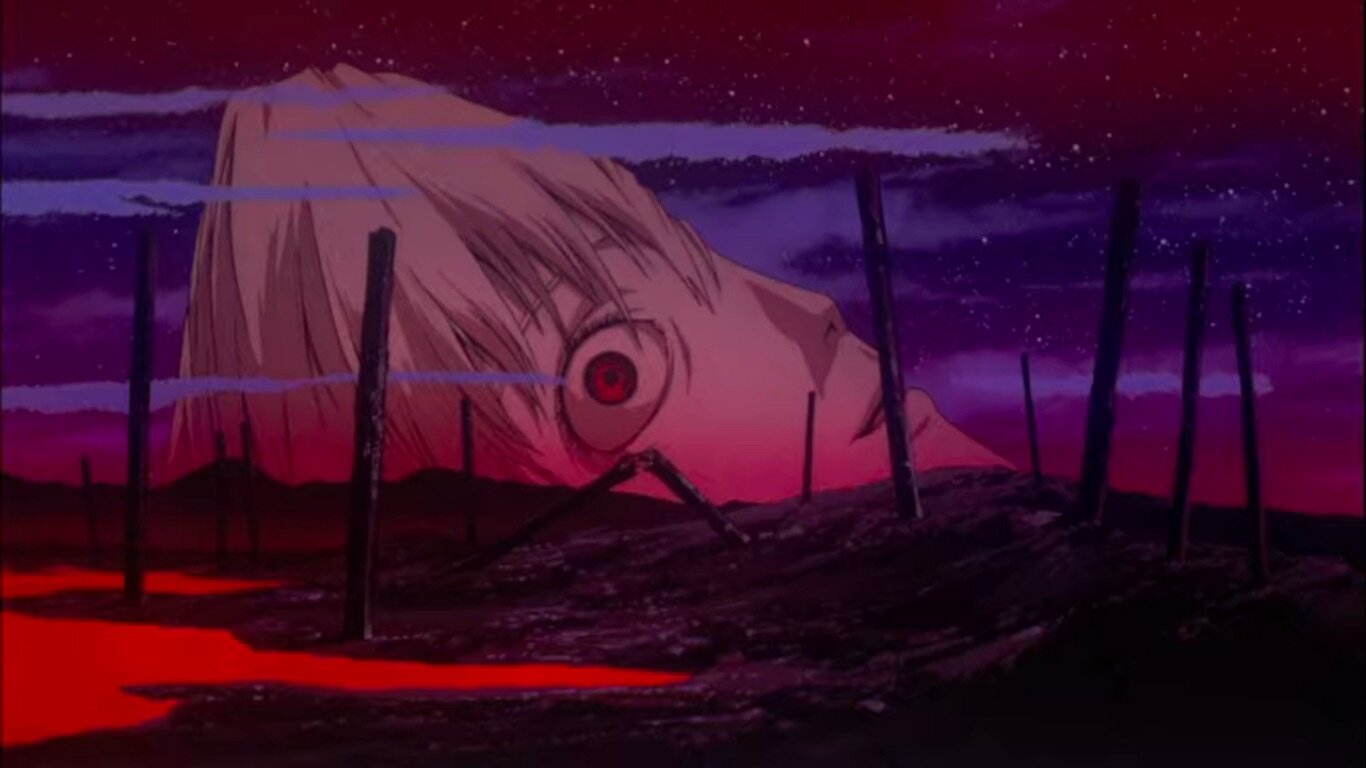

For Nonsense Apocalypse equivalent in film, we can use the punishing and authoritative motion-picture conclusion to the anime Neon Genesis Evangelion: The End of Evangelion (1997). Japanese animator Hideaki Anno’s goal is somehow to depict the apocalypse as inhumanely as possible on a scale of sublime enormity that can still be felt on an experiential human level. His method is to bifurcate the film with an intensely humanly corporal first half and a breathtakingly inhuman divine second half, making full use of Scholem’s apocalypse of a world “struck by a beam of light shining into it from an outside source.”

The film opens with an act of masturbation, a graphic and violent confirmation of the personal corporeal form, and is followed by waves of brutal human violence, gunfire and infrastructure collapse, human death and the death of markers of human civilization, the violation of bodies and the violation of spaces, which places our consciousness squarely in our own body as it involuntarily reacts and squirms to illusory imagery of violence. But the film splits after the detonation of a doomsday device and pulls into a devastatingly enormous wide shot of a non-human end of the world, electrified with glorious divine and, like Bosch, a maddening chaos of nonsense imagery. The film depicts nothing less than a universal breakdown of physical logic and a shattering of metaphysical rationality. At one point, there’s even a sequence of live action footage, a complete shattering of the aesthetic rules of the film’s universe, an absolute shift to a radically different physical reality. Evangelion is filled with overt Jewish mystic imagery, but here, profoundly, there is overt Jewish Mystic philosophy, the controversial idea of established laws meaning nothing after the coming of the Messiah. Instead of an end to Halakhic law, it is an end to the laws of physics as we see the Earth demolished via a collapse of physical logic and not, as in so many disaster films, via physical logic like the consequences of an asteroid strike, nuclear bomb, or global warming.

My whole Jewish world was steeped in the Messiah, and therefore steeped in Apocalypse. This wasn’t unique to me. Across all denominations of Judaism, to various degrees of nods to rationality, the Jewish Messiah was a constant source of awe and finality. Judaism is a religion and culture of narrative, and narrative needs direction and structure. We have ample narratives of the origins of our people, and the Messiah gives the narrative its denouement and conclusion. Regardless of the degrees of illogic that the Messiah promises to bring the world, the narrative logic of Judaism relies on the Messiah as some kind of conclusory remark on all of this.

But the life-instinct of Judaism stays stolid. It holds out on this end, shuns pushes for it, allows it to shimmer in the distance, over the horizon, another age waiting for some other one to greet it.

I’d like to give Scholem the last word on this. In the conclusion to the opening essay of his amazing book The Messianic Idea in Judaism, he issues a cautionary message to world Jewry in its over dependence on Messianic messaging:

“There is something preliminary, something provisional about Jewish history; hence its inability to give of itself entirely. For the Messianic idea is not only consolation and hope. Every attempt to realize it tears open the abysses which leads each of its manifestations ad absurdum. There is something grand about living in hope, but at the same time there is something profoundly unreal about it. It diminishes the singular worth of the individual, and he can never fulfill himself, because the incompleteness of his endeavours eliminates precisely what constitutes its highest value. Thus, in Judaism, the Messianic idea has compelled a life lived in deferment, in which nothing can be done definitively, nothing can be irrevocably accomplished. One may say, perhaps, the Messianic idea is the real anti-existentialist idea. Precisely understood, there is nothing concrete that can be done by the unredeemed. This makes for the greatness of Messianism but also for its constitutional weakness. Jewish so called existenz possesses a tension that never finds true release; it never burns itself out…”

With this quote, I imagine the thoughtful Jewish scholar of the days of yore, eyes furrowed in pain, thinking of the horrors of his present, thinking of the release of the Messianic age, thinking of the release of nothingness. And yet, he can’t give in to this release, he can’t allow himself to do so, with all the work there is yet to be done. Still, it’s a consolation and a consummation devoutly to be wished. Maybe the apocalypse fascinates us because it is the final vestige of possible thought, the last outpost of the human, beyond which we cannot even fathom. But maybe it’s the fathoming that hurts us so. Maybe we find consolation in the end to the horrible passion of thought. Maybe we find solace in Nothing.

- June 25th, 2023