Hello. How are you? (Click Email to let me know).

I’m a writer and filmmaker based in Vancouver, BC.

HERE’S MY REEL

On my filmmaker side I make narrative films and music videos. On my writing side I’ve published short stories, essays, and book reviews. I’ve also written novels, feature screenplays, and film theory that are just sitting on my computer as of now but I’d like to publish them too one day. That would be so cool. I love writing.

I’m currently researching and developing a feature film with the support of the Canada Council for the Arts.

You can read essays I’m writing as part of my research here.

I graduated from the University of British Columbia in 2018 with a BFA in Film Production and a Minor in Literature. Since then, I’ve been in VIFF’s Catalyst Program and had my work shown in festivals across the country and my writing published in magazines distributed all over North America. I’m now pursuing my MA in Cinema Studies at UBC.

This is really fun for me and I like doing it. I’m going to keep doing it. Thanks for reading. (Click Email to say you’re welcome).

Contact Me

Between Two Worlds

On Ghosts, Souls, Folklore, and The DybbukHere’s how I remember it happening:

I was maybe six or seven. My family was travelling in Nova Scotia where my Mom’s side of things first settled after moving from the old country. I think we had visited a cemetery that day which means we were probably in Sydney. I don’t know. I woke up that night in a hotel room, nestled in closely amongst everyone else or maybe I was in one of those cots you have to call up from the front desk with a blanket made from a kind of fabric that has no name. The entire room was black. There were no lights or sounds coming out from the city. The whole of the earth had dissolved into blankness. Then suddenly: form. A silver amoeba wavering out of the bathroom. I could barely look at it in that radiating dark, it shimmered in its instability. But it lumbered like a man and in slow blurring steps it leaned down to me and I saw the face of an ancient person, crumbled with time and then it disappeared and the black turned into shadows and the room became manifest again.

This never happened again but I worried about it constantly. I was terrified of ghosts. Their danger felt imminent. I thoroughly believed in monsters too but ghosts were way worse. All night creatures could kill you, that much was certain, but the most monsters could do was tear your body to shreds. I knew ghosts could do one worse — they could possess you. Ghosts would hijack your body and evaporate your soul. Not only would you effectively die but your personage would be commandeered by a new malevolent force that would take control over your reputation and your relationships. Then your consciousness would be annihilated, your soul would know no world to come. You would undergo complete religious ego-death. To me, a ghost’s violence was a specifically spiritual one that bypassed my flesh, my mind, and lunged straight for my Jewish soul.

My Jewish day school education didn’t teach much about souls beyond some casual classroom speculation. It wasn’t until recently that I read more about it and moved beyond the Christian notion I had absorbed through indirect cultural infusion. Kabbalists thought of the human soul as having three elements: The Nefesh, the Ruach, and the Neshamah (as well as several additional appendages depending on the holy workings of the body containing these souls). The Nefesh is a give-in, bestowed on every individual at birth and is considered something animal, the guider of the innate bodily desires of man, instincts and the cravings of corporality. The Ruach, a middle soul of sorts, contains our senses of morality, balance, judgements of good and evil. The Neshamah distinguishes man from all other life on earth, holding our intellect and awareness of a beyond. This aspect of our soul is nourished and grows with Torah study and unlocks from our baseness and transitions to the afterlife.

It’s a rather small step into a completely Freudian reading of the Jewish spirit where Id, Ego, and Superego replace the Kabbalic soul and my ghosts become wandering spectres of Penis Envy and I, shivering in that hotel room in the Maritimes, wracked with Castration Anxiety, protected whatever bud of a Neshamah my limited Jewish learning had grown from these malevolent spirits. Freud himself might not have necessarily disagreed with this jump either, often using “Die Seele” or “The Soul” interchangeably with Psyche, itself borrowed from Plato’s conception of the soul, itself broken into three parts of desire, reason, and an intermediary. While these might be (and certainly have been) the basis for more thoughtful comparisons than this essay, what I mean to emphasize is not necessarily proof of a human soul but that, surviving through millennia and shifting from philosophical to esoteric mystical to academic psychological, there endures the idea of a non-physical entity of true personhood, of essential you-ness, and regardless of whether this entity outlasts the flesh and preserves one forever in glowing immortality, this is a culture spanning concept that has outlasted every phase of every religion or movement or school of thought. An inextricable life force that is you perhaps even more so than your body. I had a specifically spiritual panic at the thought of this being under attack. I would have gladly been gobbled up by any under-the-bed monster if it meant retaining my enduring me-ness.

There are a few references to ghosts in the Tanach. In one of the law-giving chapters it’s decreed that it is forbidden to conduct seances and attempt to communicate with the dead. This was famously disregarded in the Book of Samuel when King Saul, with the help of the Witch of Endor, summoned the recently dead Samuel’s invisible spirit for help with defeating the philistines. But to my knowledge there’s no biblical reference to wandering malevolent spirits. It took the transformation of doctrine into folk religion for the rise of ghosts and demons. This notion of personhood made from definite matter (be it spiritual or cranial), developing independent in multiple different cultures, time periods, and spectrums of metaphysical skepticism, easily shifts into a completely externalized entity with attributes, abilities, and rules governed by the unstoppable wanderings of a human imagination. Its here that the ideas and ideals of philosophy and religion are handed over to the people and twisted into their poignant and powerful needs fed by belief systems beyond those intended by their community leaders. Inherited concepts from neighbouring peoples, explanations for new phenomena, responses to events that move faster than doctrine and dogma. Religious authorities cannot keep up with the multiplying myriad beliefs of their folk but the grand osmosis of migration and diaspora force doctrine and natural law to give way to lore, a grand and sprawling mythology that warbles with the shimmering instability of my ghost.

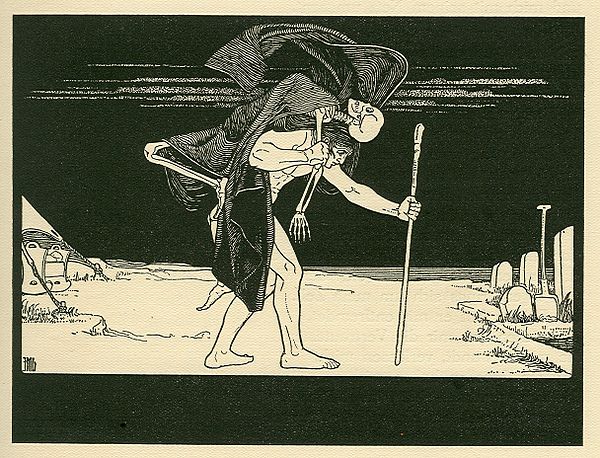

I am just as much a part of this developing mythology as my ancestors who built the Jewish superstitious mythology were. Just as much as you are. I say my ghosts because my ghosts followed my rules. Your ghosts followed yours. But if we were to meet and discuss the various systems of our super-natures we wouldn’t find ourselves arguing. Rather the exchange of ideas bleed into each other, comfort or disturb one another, without clashing principals or contradictions. Folklore is a zone that is built of contradictions, that thrives on them for it is reliant on the fundamental mystery of the universe that forever remains unknowable. Either one of our suppositions could prove right. Folklore morphs out of the dark corners of forests, deserts, mountains, and crossroads where scientific method cannot tread and only the imagination can explain. And so the folklore of all culture lives well and thrives forever after; no Wendigo or Baba Yaga or Djinn could ever fully be disproved as long as there are imaginations to keep them alive. They were born and they grow and they endure in the never-dying backwoods of the mind, the bleeding circles between the imaginary and the rational, the perpetual and ever-lasting “what-if.”

I find folk horror particularly frightening for this reason; it feels like the counterpoint to cosmic horror. Both imply threats that emerge out of our cultural non-understanding of the universe, the parts of reality that logic cannot illuminate because they either can’t be comprehended by human minds (cosmic horror) or elude established methods of reason, cause and effect, and materialism (folk horror). They are two sides of the same coin. Where as cosmic horrors are external mysteries projected inward and their fearful qualities and danger arise out of the limited capacities of our ability to catalogue them with our conception of reality, folk horror is an externalization of inner mysteries projected outward into the world, the secrets of the truth of the human mind and spirit externalized as spectres of possession, corruption, and desire.

And so this is what I did. I externalized the mystery of consciousness and personality into a creature made up of the fear of the unknown in the dark grottos of my self and decided that the fear I felt at this creature came from its threat toward my “self,” my me-ness. I arrived at a perfectly rational terror of a wandering lost soul. I didn’t learn until years later that this idea of a wandering spirit that could expunge my ego if given the chance was a thoroughly Jewish idea that manifested in the form of a creature I still can’t pronounce the name of without spitting three times. Just to be sure. The Dybbuk.

The Dybbuk first appeared in writing in the early 17th century in an anthology of Eastern European Jewish legends. It describes a malicious spirit which could manifest as the dislocated soul of a dead person (in this case the story is told of a young man possessed by the spirit of a rival) or, more purer, a demonic entity that never was human and longs to be. This evil wandering formless being can possess the body of a living victim and, to quote Gershom Scholem, “cleaves to their soul…representing a separate and alien personality.”

In a wonderful compendium of Ashkenazi superstitions, American scholar Joshua Trachtenberg describes the peculiar and wide ranging desires of demons in Jewish mythology. He explains that “demons may make their homes in man’s body. This view found its rationalization in the legend that the demons, created on the eve of the Sabbath, are bodiless. Since all creation is engaged in a quest for perfection, all things striving to attain the next higher degree of being, the demons, too, are perpetually seeking to acquire the body of man, their greatest desire being for that of a scholar, the highest type of human.”

There’s something terrifically Jewish about this creature, a diasporic wanderer that seeks only to elevate its existence. From that reading maybe we could make special note that the emergence and rise of the Dybbuk figure (though the notion “evil spirits” had been around since the temple period) occurred during the Jewish 17th century, one of the most traumatic centuries in Eastern European Jewry before the Holocaust. Facing several waves of massacres from the Cossacks, Swedes, and Ukrainians as well as the widespread movement and subsequent apostasy of Messianic claimant Shabbotai Tzvi, the communal and spiritual life of Eastern European (and specifically Polish-Lithuanian) Jews would shatter and transform. Their intellectual output dampened and fragmented significantly leading either to stricter authority from the Orthodox Rabbinic elite or the proliferation of mystic ideas as the Hasidic movement pushed Kabbalism out of ascetic esoterica and into the hands of the masses, an anarchic act to the perspective of the established normative Rabbinic order. Maybe the Dybbuk is an externalization of a people whose cores of settlement and belief were being obliterated, who became formless spectres of self from the faltering and traumatically changing sense of that essential “me-ness.” And if Freud chimed in on our cultural psychoanalysis as this Jewish demon grew in stature he would point out, as he did in his 1923 essay “A Neurosis of Demoniacal Possession in the Seventeenth Century,” that “what in those days were thought to be evil spirits to us are base and evil wishes, the derivatives of impulses which have been rejected and repressed. In one respect only do we not subscribe to the explanation of these phenomena current in mediaeval times; we have abandoned the projection of them into the outer world, attributing their origin instead to the inner life of the patient in whom they manifest.” The Dybbuk could be seen as a projection of a bodiless and shapeless and fragmented people who were told repeatedly to the point, no doubt, of internalization of their insidious cancer-like nature, that they would grow and infect and take over a nation-state if they were allowed to. And so the Jews summoned the Dybbuk to haunt themselves, a demon and Dæmon of their own, a caricatured Jew as described by their oppressors and illustrated by a people that did not know what they themselves looked like and so it took the form of nothing, a formless phantom of personhood.

The Dybbuk makes us confront a disembodied ontology and I think this idea is particularly frightening to Jews. For millennia Jews were a wandering people without a point of origin and as the fluxes and flows of nation states and empires and dynasties ebbed throughout Europe, the Jews were exiled and imprisoned and their spiritual identity was forced to reconcile with these systems of massive change without a centre to hold them. I think of this creature as the ultimate Jewish monster, a force of disembodiment that itself is disembodied, that personifies an immediate absence and inflicts that state on its victims via a contagion of will. The Dybbuk is a force of presence (they are, after all, the souls of specific people) and a force of absence: non-physical and disorganized. And this is exactly what they threaten, the continued presence of your body and the eternal absence of that essential you-ness. An uncanny living contradiction.

Within the theology of the proliferating Jewish mysticism of this era came with it a tension between the embodied and the disembodied. Kabbalism paid special attention as it wrote out imaginative interpretations of the Jewish creation myth to the creation of gross matter and physicality to “clothe” the initial pure spiritual matter of the remnants of God present in our physical reality. The Dybbuk, as a Gnostic agent of chaos, violates this clothing of physical matter, the building block of our plane of reality, with unique access to the spark of life and personality within man. Kabbalism sees, given the omnipotent presence of God, a potential breath of life that is universal. God too is a force of presence and non-presence, a demiurgical artisan that organizes the physical material that makes up the essence of the universe which contains his own divine spiritual matter yet he himself is retracted and beyond a vault in reality. We can see the Dybbuk as a bull in this artisan’s studio, bypassing the physical fashioning that protects that basic spiritual material and disorganizing all the demiurgical God sought to maintain.

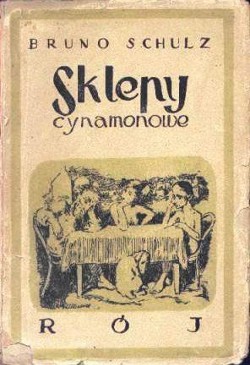

In Polish-Jewish writer Bruno Schulz’s semi-autobiographical fantasia Street of Crocodiles, the narrator’s enigmatic father expresses a belief system not unlike what I’m describing here. Slightly odd at the beginning of the novel, a fully insane magus-like mad scientist by the end, he delivers a series of sermons which elaborate on this Kabbalist thought, particularly sinister and intriguing if thought of as coming from the perspective of a Dybbuk, a leap not all too difficult to make:

“The whole of matter pulsates with infinite possibilities that send dull shivers through it. Waiting for the life-giving breath of the spirit, it is endlessly in motion. It entices us with a thousand sweet, soft, round shapes which it blindly dreams up within itself….it is a territory outside any law, open to all kinds of charlatans and dilettante, a domain of abuses and of dubious demiurgical manipulation. Matter is the most passive and most defenceless essence in the cosmos. Anyone can mold it; it obeys everybody. All attempts at organizing matter are transient and temporary, easy to reverse and to dissolve. There is no evil in reducing life to other and newer forms. Homicide is not a sin. It is sometimes a necessary violence on resistant and ossified forms of existence which have ceased to be amusing… there is no dead matter…lifelessness is only a disguise behind which hide unknown forms of life.”

![]()

First edition cover of The Street of Crocodiles (as Cinnamon Shops)

First edition cover of The Street of Crocodiles (as Cinnamon Shops)

In 1920, S. Ansky’s play The Dybbuk, or Between Two Worlds premiered in Warsaw. Set in the Pale of Settlements, another of the arbitrary tools of disembodiment set upon Eastern European Jews, the play tells the story of a community besieged by a malevolent force from the Jewish beyond as a Dybbuk, originating from the spirit of a maligned lover, possesses his would-be-bride after a consult with Kabbalist magic goes wrong and kills him. The play itself is dramatic and stunning but I’m especially moved by the 1937 film adaptation. Modulating the plot slightly, the film tells the story of a young student, Chanan, who falls in love with Leah, the daughter of a rich Rabbi. Knowing the Rabbi won’t agree to wed his daughter to someone as poor as him, Chanan obsessively studies Kabbalah to find some magical way to change his circumstances. But it’s too late, Leah is promised to a rich man’s son. In a haunting scene of desperation, he summons a demon in a Mikvah, a Jewish ritual bath, to help him but the shock of witnessing a tear in reality kills him. He returns soon after as a Dybbuk and possesses Leah to stop the wedding. This is represented is one of the more beautiful and hypnotic scenes I’ve seen in a film. In a “dance with death,” the whole of the town is stunned into a delirium and lurch to a haunting klezmer waltz as the spectre of death emerges from the crowd, grabs Leah and, flashing its fractured personhood, seemingly hypnotizes her and marches her off screen to possess her body.

This film fascinates me for a number of reasons beyond its own artistic merits. For one, it was the last Yiddish-language Polish-produced film made before the Holocaust and so I think its narrative featuring that spectre of communal, personal, and spiritual obliteration is particularly poignant considering something like 40% of the cast and crew would be killed in the years to come. But I’m particularly taken by the story of its director, Michał Wasyński.

Michał Wasyńsky was born Moshe Waks, a Jew in a small town in the Pale of Settlement, the son of a blacksmith and a poultry trader. After being expelled from yeshiva, he moved around Eastern and Central Europe before finding himself as an assistant director in the burgeoning German film industry. Waks moved to Warsaw in the 20s a changed man. He now went by a new decidedly non-Jewish name, Michał Wasyńsky, and converted to Catholicism and for the rest of his life proclaimed to be a Polish prince. His prestige amongst his peers was unquestioned. But even the famous European elite never knew the truth of his origins. As he directed 25% of Polish films in the 30s, cavorted with the likes of Orson Welles, Audrey Hepburn, Sofia Loren, Ava Gardner, and more, produced some of the largest productions of the era including The Fall of Rome (1964) where he oversaw the creation of the largest set in film history up to that point, he maintained his invented aristocratic persona. He never publicly acknowledged his past even until his death in 1965. Once he wrote in his diary: “It does me good not to know who I am. I have blocked all the paths I might take, locked all the doors and fallen silent.”

I think of him expunging his personhood in the 20s, expelling the spark of his original me-ness and subsuming himself with a new one. Roman-Catholic royalty, a new name, a new personality. Forever a presence of absence, a personhood bifurcated and baptized anew. The spiritual matter in him fundamentally changed, he possessed his own soul, exorcised his upbringing and emerged reborn. He manifested a Dybbuk for himself. He became his own wandering spirit.

But in 1937 he returned to the Judaism of his youth. One final send off before departing from it forever after.

And so when I watch this sinister brooding film, I think of him merged indelibly with each frame. I imagine him in his shtetl as he shoots this constructed one, those far off lands of the Jewish past, Jewish-only villages of hardship and whimsy. Fiddlers on roofs and foolish wise-men, a theme and a moral at every rooster caw, every back-broken milkman. But no shtetl stands anymore — they were blown apart and burned down not long after Moshe Waks came bursting out of his own. One day, Waks sprinted from his shtetl headlong into a different caste altogether, the European show business. Did he see there how carefully they polished reality? Did he see how cheap and fractured the sets they shot were but how immaculate they fused together on screen? Orchestrated by an army of a hundred disparate conflicting personalities that shuffled these sets together, slapped stage makeup onto the ghostly faces of early film actors, cranked film through a camera, not too fast they thought, steady, steady, steady on and onto the crystals buried in that celluloid burned the work of these people and it glowed on screen. One screen, several perfect instances, a single burned image, fused like steel points. Perfect, thought Moshe Waks, perfect he thought as he gathered together the far reaching mass of his Judaism, perfect as the thought of generations of pogroms, the burgeoning street gangs of National Socialists, the haunting spires of Catholic churches burbled in the iceberg of his brain and he found a way to purge that threat and he stood before his camera, he spread wide the wings of its iris and it burned Michał Wasyński into film. And he saw how he wouldn’t have to let reality fly in the loose fate of conquering nations. No longer a wandering Jew— a conqueror himself! The diasporic masses of his neighbours, they plodded along from one nation-state to the next, exiled and driven out by horseback. But now — no more! He gathered reality in his arms like he saw his Mother’s chickens do to their babies back in the shtetl, he gathered reality in his warm arms and he burned it into place. Just like so. The whir of the cameraman’s steady, steady, steady arm sounded like an itch he was scratching.

And then in 1937, Michał Wasyński stepped back into the Shtetl, this time with his immaculate reality machine, a summoning device perhaps, one final ritual to shield his new inhabiting spirit from any exorcism perhaps. And his original host spirit let out one final call before obliteration, one final lilting Yiddish cry. And so he made The Dybbuk, a word too horrifying for a Jew to say out loud, lest they summon that spectre, and maybe he was horrified too. Maybe all the trip-wires of his innate Jewish superstition snapped and exploded as he stepped back into the world of his original soul and that’s why he shot the film with such a slow sinister trance of a camera in creeping tip-toes forward and lolling sideways pans of Jewish crowds. And he rest the film on a bed of Jewish melodies that pierce into brief shrieking cries in their final syllables, that distinctive Yiddish yelp, a long low baritone and the screech of a soprano as the word leaves the earth. It is a sick screaming bat cry, the cry of that child’s choir singing an erotic psalm in his film, that unearthly stare into the middle distance that each character falls into in his film, and The Dybbuk becomes a drifting slowly fading world on a world, neither more real than the other, directed by two souls at war within a single body. The Jewish boy that couldn’t bare to listen to his Rabbi anymore and the Polish Prince, the essence of his original soul altered and hidden indelibly.

And I think I know how he felt. I know how it feels to run from the Jews and tiptoe back, to creep back into a world with a Jewish anxiety spiking in your Jewish lungs, to look on their praying with horror, horror that the faces they make could be made on your own. To look at it like the boy in the movie, with terror in his eyes, the whites of them jelly, the pupils and irises jet, seeing his friend summoning demons naked inside a mikvah, his sweat turning to steam, turning to panic that will stop his heart and I am outside that window gawking with my eyes like jelly at the unstoppable roll of our faith toward doom.

And I see myself as the Jewish bride in the film, amongst a crowd of Jewish peers who she saw as hypnotized and jerking like zombies to that klezmer waltz, and as I stared awkwardly into the crowd there emerged an angel of death, a spectre of absence and its this absence that I longed for. A Judaism at once inextricable and invisible and I grabbed this spectre and let it march me away.

Now I think I know what he felt as he set out to make his movie as I sit in a circle of Jewish books and make mine, throwing Hebrew letters at my brain, taking quiet deliberate steps back toward the spark of my self that I left, back toward the essential me-ness. Have I tried to make a magic circle? To exorcize that demon of absence I had summoned years ago? Will it work? Will I be able to go back to see what had happened after my body had left that spiritual matter it had clothed years ago? Can I go back to hold it and myself in two hands, weighing to see how its changed while I’ve been gone?

- May 28, 2023